Low-income neighborhoods with lots of concrete and few trees can heat up faster than surrounding areas. AP Photo/Richard Vogel

In this Article:

- How do large temperature swings affect human health?

- Why are low-income neighborhoods more vulnerable to temperature variations?

- What racial disparities exist in exposure to daily temperature swings?

- How does the urban heat island effect increase temperature swings in cities?

- What can communities do to reduce health risks from temperature swings?

How Temperature Swings Impact Your Health

by Shengjie Liu and Emily Smith-Greenaway, USC Dornsife College.

This summer has shown how quickly high temperatures can pose serious health risks, with record-breaking heat waves claiming thousands of lives around the world.

However, it’s not just high and low temperatures that matter. How many degrees the temperature swings within a day – the daily temperature variation – itself poses health risks.

Studies have found that days with larger than normal temperature swings can increase asthma flare-ups and hospitalizations for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, leading to an overall higher death rate than normal. One study, based on data from 308 cities from 1972 to 2013, estimates that 2.5% of deaths in that time could be attributed to large daily temperature swings.

Although humans can live in a wide range of ambient temperatures, a dramatic shift in temperature can tax multiple systems in the body, including the immune, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems. It can be especially taxing on very young and older individuals, who are generally more vulnerable to harsh climates.

We mapped daily temperature variations at the neighborhood scale across the U.S. to get a better picture of where these temperature swings are highest and who is most affected. The results highlight how poverty and a legacy of discriminatory practices have left racial minorities and low-income residents in neighborhoods with more dramatic temperature differences through the day.

What affects temperature swings?

Large night-to-day temperature swings are more common in some regions, such as the U.S. Southwest, but they can also vary over short distances depending on the landscape and what’s known as the urban heat island effect.

For example, the ocean can mitigate rapid temperature changes since water can absorb a lot of heat before it gets hot. The Greater Los Angeles area is a case in point. Santa Monica, a coastal community in Los Angeles County, has much smaller temperature swings then more inland neighborhoods in the county, like downtown Los Angeles.

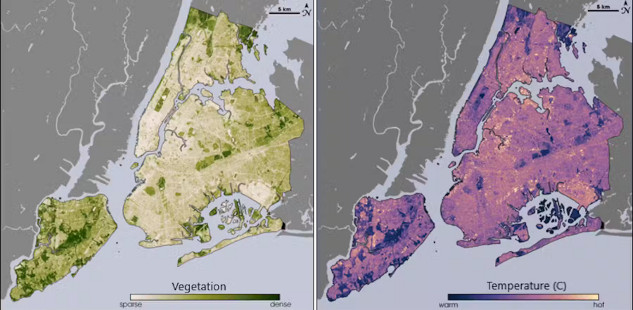

Comparing maps of New York City’s tree cover and temperature differences shows the cooling effect of parks and neighborhoods with more trees. NASA/USGS Landsat

Green space, like forested parks, can also reduce temperature swings. Urban trees and vegetation can keep neighborhoods cooler, reducing the temperature volatility.

Who faces the greatest temperature swings?

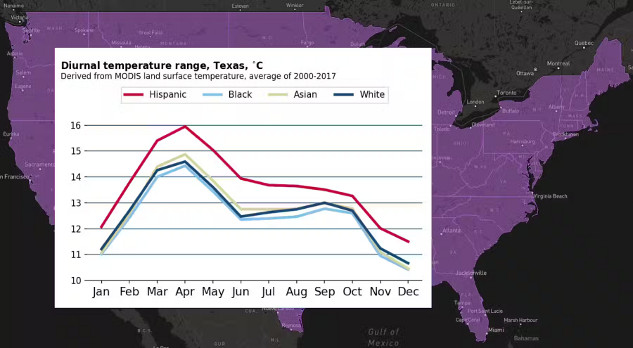

Using NASA’s satellite data between 2000 and 2017, we cross-checked the daily temperature variation with the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey demographic data at different census tracts to see how race and ethnicity, income, and age affected exposure to daily temperature variations across all 50 states.

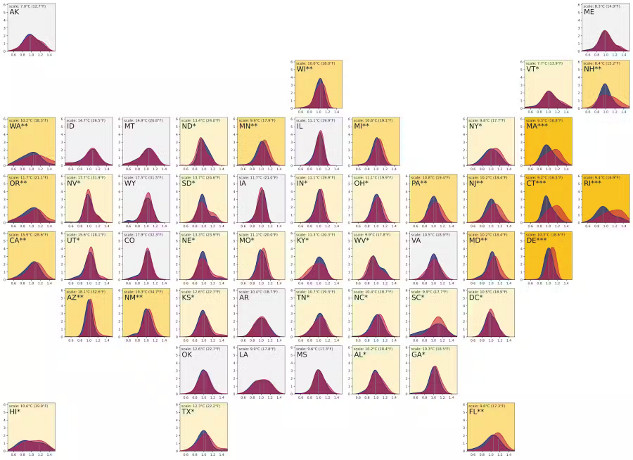

We found that, of the three demographic factors, exposure to daily temperature variation is the most unequal by race and ethnicity, followed by income. Age mattered the least.

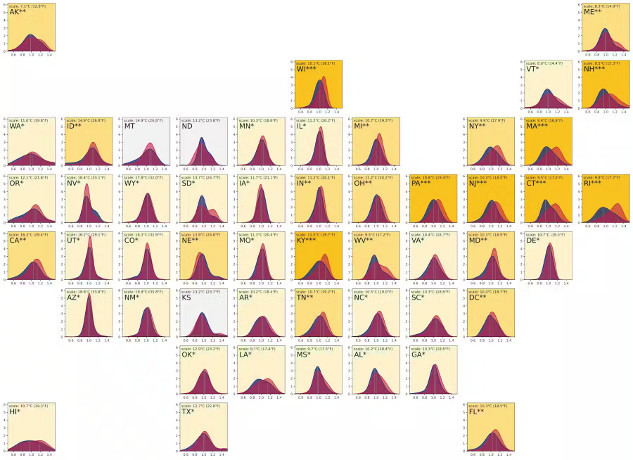

Differences by race: Maps of the average daily temperature variation in each state by race. The darker the yellow square, the wider the inequality. In each state’s chart, the blue area reflects white populations, and red reflects nonwhite populations. Shengjie Liu, CC BY-ND

In the state with the greatest disparity, Rhode Island, Hispanic and Black populations experienced, on average, daily temperature swings of 31.2 degrees Fahrenheit (17.3 degrees Celsius) in May, while the average daily temperature variation for white populations was 25.8 F (14.3 C). That’s a 5.4 F (3 C) difference between the groups.

The contrast between low-income and high-income groups in Rhode Island was 28.6 F (15.9 C) compared with 24.5 F (13.6 C), a 4.1 F (2.3 C) difference. The difference was negligible among age groups, at 1.8 F (1 C).

Differences by income: Maps of the average daily temperature variation in each state by income. The darker the yellow square, the wider the inequality. In each state’s chart, the blue area reflects high-income populations, and red reflects low-income populations. Shengjie Liu, CC BY-ND

Among the 50 states, we saw significant differences by race and ethnicity in 46 states, by income in 39 states, and by age in 15 states. In general, daily temperature swings were highest in western states, particularly in late spring and summer.

The fact that minority populations are disproportionately living in neighborhoods with wider temperature swings confirms yet another dimension of inequality in vulnerability to climate change.

Temperature swings widen with climate change

There is also evidence that temperature swings will get more dramatic over time. From the 1950s to the 1980s, records show shrinking temperature swings globally. Since the 1990s, however, research shows temperature swings have widened, potentially affecting all life on Earth.

An interactive map available at the following link shows the average daily temperature swings for each state by race and ethnicity: skrisliu.com/dtvus/map.html, CC BY

Studies suggest these temperature swings will continue to widen as greenhouse gas emissions, largely from burning fossil fuels, continue to raise global temperatures. And with those increases will come more premature deaths. Under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s highest emissions scenario (RCP 8.5), which projects conditions in a world that burns increasingly large amounts of fossil fuels, future temperature swings are projected to increase by as much as 2.9 F (1.6 C) by the end of the century.

There are ways to reduce the risk, starting with cutting greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, power plants, livestock and other sources.

Communities can also take steps to reduce low-income and minority neighborhoods’ exposure to temperature swings by increasing tree cover and using light coatings on roofs to reflect heat away from buildings. They can also provide support programs to help people who can’t otherwise afford to install or power cooling or heating equipment.![]()

Shengjie Liu, Ph.D. Candidate in Spatial Sciences, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Emily Smith-Greenaway, Associate Professor of Sociology, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Article Recap:

This article discusses the health risks associated with large daily temperature swings and their disproportionate impact on low-income and minority communities. It highlights how urban environments, racial disparities, and climate change exacerbate these risks, and explores ways to mitigate harm through green spaces and climate policies.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books:

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma

by Bessel van der Kolk

This book explores the connections between trauma and physical and mental health, offering insights and strategies for healing and recovery.

Click for more info or to order

Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art

by James Nestor

This book explores the science and practice of breathing, offering insights and techniques for improving physical and mental health.

Click for more info or to order

The Plant Paradox: The Hidden Dangers in "Healthy" Foods That Cause Disease and Weight Gain

by Steven R. Gundry

This book explores the links between diet, health, and disease, offering insights and strategies for improving overall health and wellness.

Click for more info or to order

The Immunity Code: The New Paradigm for Real Health and Radical Anti-Aging

by Joel Greene

This book offers a new perspective on health and immunity, drawing on principles of epigenetics and offering insights and strategies for optimizing health and aging.

Click for more info or to order

The Complete Guide to Fasting: Heal Your Body Through Intermittent, Alternate-Day, and Extended Fasting

by Dr. Jason Fung and Jimmy Moore

This book explores the science and practice of fasting offering insights and strategies for improving overall health and wellness.