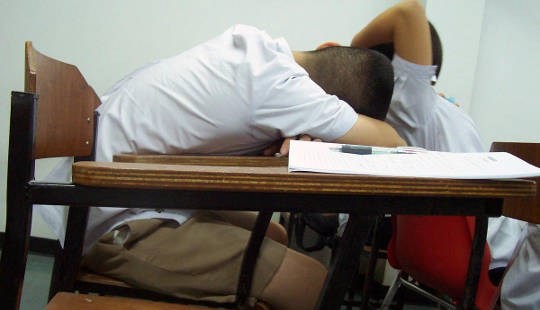

Millions of high schoolers are having to wake up early as they start another academic year. It is not uncommon to hear comments from parents such as, “I have a battle every morning to get my teenager out of bed and off to school. It’s a hard way to start every day.”

Sleep deprivation in teenagers as a result of early school start has been a topic of concern and debate for nearly two decades. School principals, superintendents and school boards across the country have struggled with the question of whether their local high school should start later.

So, are teenagers just lazy?

I have been researching the impact of later high school start times for 20 years. Research findings show that teens' inability to get out of bed before 8 a.m. is a matter of human biology, not a matter of attitude.

At issue here are the sleep patterns of the teenage brain, which are different from those of younger children and adults. Due to the biology of human development, the sleep mechanism in teens does not allow the brain to naturally awaken before about 8 a.m. This often gets into conflict with school schedules in many communities.

History of school timing

In the earliest days of American education, all students attended a single school with a single starting time. In fact, as late as 1910, half of all children attended one-room schools. As schools and districts grew in size in the late 1890s-1920s, staggered starting times became the norm across the country.

In cities and large towns, high school students went first, followed by middle schoolers and then elementary students.

Here’s what research shows

Research findings during the 1980s started to cast a new light on teenagers' sleep patterns.

Researcher Mary Carskadon and others at Brown University found that the human brain has a marked shift in its sleep/wake pattern during adolescence.

Researchers around the world corroborated those findings. At the onset of puberty, nearly all humans (and most mammals) experience a delay of sleep timing in the brain. As a result, the adolescent body does not begin to feel sleepy until about 10:45 p.m.

At the same time, medical researchers also found that sleep patterns of younger children enabled them to rise early and be ready for learning much earlier than adolescents.

In other words, the biology of the teenage brain is in conflict with early school start times, whereas sleep patterns of most younger children are in sync with schools that start early.

Biology of teenage brain

So, what exactly happens to the teenage brain during the growth years?

In the teens, the secretion of the sleep hormone melatonin begins at about 10:45 p.m. and continues until about 8 a.m. What this means is that teenagers are unable to fall asleep until melatonin secretion begins and they are also not able to awaken until the melatonin secretion stops.

These changes in the sleep/wake pattern of teens are dramatic and beyond their control. Just expecting teens to go to bed earlier is not a solution.

I have interviewed hundreds of teens who all said that if they went to bed early, they were unable to sleep – they just stared at the ceiling until sleep set in around 10:45 p.m.

According to the National Sleep Foundation, the sleep requirement for teenagers is between 8-10 hours per night. That indicates that the earliest healthy wake-up time for teens should not be before 7 a.m.

A recent research study that I led shows that it takes an average of 54 minutes from the time teens wake up until they leave the house for school. With nearly half of all high schools in the U.S. starting before 8:00 a.m., and over 86 percent starting before 8:30 a.m., leaving home by 7:54 a.m. would be a challenge for most teens in America.

What happens with less sleep

Studies on sleep in general, and on sleep in teens in particular, have revealed the serious negative consequences of lack of adequate sleep. Teens who are sleep-deprived – defined as obtaining less than eight hours per night – are significantly more likely to use cigarettes, drugs and alcohol.

The incidence of depression among teens significantly rises with less than nine hours of sleep. Feelings of sadness and hopelessness increase from 19 percent up to nearly 52 percent in teens who sleep four hours or less per night.

Teen car crashes, the primary cause of death for teenagers, are found to significantly decline when teens obtain more than eight hours of sleep per night.

What changes with later start time?

Results from schools that switched to a late start time are encouraging. Not only does the teens' use of drugs, cigarettes, and alcohol decline, their academic performance improves significantly with later start time.

The Edina (Minnesota) School District superintendent and school board was the first district in the country to make the change. The decision was a result of a recommendation from the Minnesota Medical Association, back in 1996.

Research showed significant benefits for teens from that school as well as others with later start times.

For example, the crash rate for teens in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in 2013 dropped by 70 percent in the first year after the district adopted a later high school start.

At this point, hundreds of schools across the country in 44 states have been able to make the shift. The National Sleep Foundation had a count of over 250 high schools having made a change to a later start as early as 2007.

Furthermore, since 2014, major national health organizations have taken a policy stand to support the implementation of later starting time for high school. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have all come out with statements that support the starting time of high schools to be 8:30 a.m. or later.

Challenges and benefits

However, there are many schools and districts across the U.S. that are resisting delaying the starting time of their high schools. There are many reasons.

Issues such as changing transportation routes and altering the timing for other grade levels often head the list of factors making the later start difficult. Schools are also concerned about afterschool sports and activities.

Such concerns are valid. However, there could be creative ways of finding solutions. We already know that schools that were able to make the change found solutions that show “out of the box" thinking. For example, schools adopted mixed-age busing, coordinated with public transport systems and expanded afterschool child care.

I do understand that there are other realistic concerns that need to be addressed in making the change. But, in the end, communities that value maximum development for all of its children would also be willing to grapple with solutions.

After all, our children’s ability to move into healthy adult lives tomorrow depends on what we as adults are deciding for them today.

About The Author

Kyla Wahlstrom, Senior Research Fellow, University of Minnesota

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books:

at

Thanks for visiting InnerSelf.com, where there are 20,000+ life-altering articles promoting "New Attitudes and New Possibilities." All articles are translated into 30+ languages. Subscribe to InnerSelf Magazine, published weekly, and Marie T Russell's Daily Inspiration. InnerSelf Magazine has been published since 1985.

Thanks for visiting InnerSelf.com, where there are 20,000+ life-altering articles promoting "New Attitudes and New Possibilities." All articles are translated into 30+ languages. Subscribe to InnerSelf Magazine, published weekly, and Marie T Russell's Daily Inspiration. InnerSelf Magazine has been published since 1985.