It’s a universal question: how do we teach a child to behave? Well-known and widely used strategies include the use of positive reward stickers or gold stars, or negative time-outs or detentions. These are techniques based on the idea that behaviour can be controlled and modified with reinforcement systems of rewards and sanctions, and can be useful ways to motivate children or moderate their behaviour.

But if these external mechanisms to condition behaviour really worked, we would not need prisons and there wouldn’t be a 50% re-offending rate. Nor do they resolve mental health issues, which are often the source of behavioural problems. Children also “habituate” to reward systems, which means they lose their effectiveness in motivating children to behave.

Similarly, fear of punishment can lead to children relying on innate survival mechanisms such as disassociation (not caring) or becoming reactive (aggressive) in an attempt to compensate. Rewards and sanctions don’t work for children with additional needs because they depend upon a capacity to mentally envisage and understand the consequences of behaviour. They require an ability to delay gratification and a capacity to regulate emotional needs. Rewards and sanctions rely on a calm, fully functional and rational mind to operate successfully.

A more effective way of managing behaviour is a technique called “emotion coaching”. This system reflects the evidence that the most successful programmes for improving behaviour are those that focus on the emotional and social causes of difficult behaviour and proactively teach social and emotional skills.

Emotion coaching emphasises emotional regulation rather than behaviour modification. It views all behaviour as a form of communication, making an important distinction between children’s behaviour and the feelings that underlie their actions. It is about helping children to understand their varying emotions as they experience them, why they occur, and how to handle them.

The system is comprised of two key elements – empathy and guidance. The empathy part involves recognising and labelling a child’s emotions, regardless of the behaviour, in order to promote emotional self-awareness. The circumstances might also require setting limits on appropriate behaviour and even consequences, but key to this process is the guidance, helping a child to recognise and label certain emotions and feelings, such as “angry” or “sad”.

This comes from engagement with the child in problem solving to support their ability to self-regulate and adopt alternative behaviours, and prevent future transgressions. But only when their brains are in a receptive state for such problem solving.

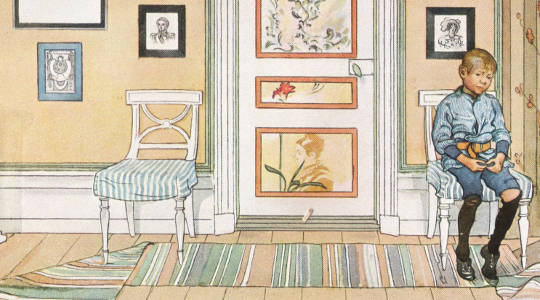

When managing behaviour, adults usually rely on reason to distract or dissuade a child. But when a child is in an emotional state, particularly an intense one, they are unable to engage with the more rational parts of their brain. Their minds and bodies are “locked” in a survival state of flight or flight such as the classic “toddler tantrum”, even when the response has been triggered by something such as thwarted desire.

Children in an emotional state need to be returned to a relaxed, calm state before we can reason with them. If we propose solutions before we empathise, it’s like trying to build a house before a firm foundation has been laid. Empathy helps the child to calm down so they are more open and able to reason, helping to create neural connections in the rational brain to become an efficient manager of emotion.

You may think that empathising with children will lead to an endorsement of bad behaviour. But emotion coaching also involves establishing the boundaries of acceptable behaviour and setting limits. You can condone the feeling underlying the behaviour, but not the behaviour itself.

Talking it over

The clear evidence from a pilot study we carried out is that emotion coaching in schools can reduce exclusions, improve academic attainment and enhance mental health. One ten-year-old boy diagnosed with behavioural difficulties would often shout, scream and hit. Instead of ignoring him or removing him from the class, the teacher communicated with the boy about how he was feeling. “It looks like you are really angry. I think you’re fed up with having to wait your turn. I understand that.”

This helped to calm him more quickly. The teacher could then talk to him about the school rules and suggest strategies to manage his feelings and behaviour. After experiencing this kind of coaching, the boy began to self-regulate both his emotions and behaviour?. He would approach the teacher and say, “I’m angry because Tom called me thick.” He developed greater empathy about the impact of his behaviour and would apologise to his peers. He was no longer at risk of exclusion.

Emotion coaching can be used for all ages - from babies to teenagers. Research shows parents who emotion coach have children who achieve more in school, have more friends, experience fewer behavioural problems and are more resilient. It is a way of telling a child that they are supported, cared about, understood and respected. It also communicates that not all behaviours are acceptable, that they cannot always get what they want and that they need to moderate how to express feelings and desires.

In this way, a child learns to empathise, read the emotions and social cues of others and control impulses. They are able to self-calm and self-regulate, delay gratification, motivate themselves and better cope with life’s ups and downs – essential skills for when they are grown ups, too.

About The Author

Janet Rose, Doctoral Supervisor, Bath Spa University

Rebecca McGuire-Snieckus, Lecturer in Psychology, Bath Spa University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon