It is perhaps one of the most controversial debates in sexual function: is there or isn’t there a G-spot? And if there is, how do we find it?

The G-spot is a purported highly erogenous area of the vagina that, when stimulated, may lead to strong sexual arousal and orgasm. Although the concept of vaginal orgasms has been around since the 17th century, the term G-spot wasn’t coined until the 1980s. The G-spot is named after Eric Grafenberg, a German gynecologist, whose 1940s research documented this sensitive region within the vagina in some women.

The controversy surrounding the G-spot comes about because there is no consensus over just what the G-spot is, and while some women can orgasm through stimulation of the G-spot, others find it incredibly uncomfortable.

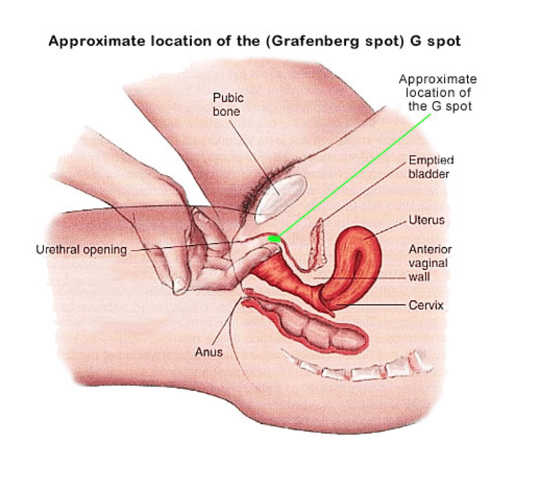

Where is the G-spot?

The G-spot lies on the anterior wall of the vagina, about 5-8cm above the opening to the vagina. It is easiest to locate if a woman lies on her back and has someone else insert one or two fingers into the vagina with the palm up. Using a “come here” motion, the tissue surrounding the urethra, called the urethral sponge, will begin to swell.

This swelling area is the G-spot. At first, this touch may make the woman feel as though she needs to urinate, but after a few seconds may turn into a pleasurable sensation. For some women, however, this stimulation remains uncomfortable, no matter how long the stimulation continues.

The G-spot orgasm and female ejaculation

Physiological responses from a G-spot orgasm differ to those responses seen in clitoral orgasms. During clitoral orgasms, the end of the vagina (near the opening) balloons out; however, in G-spot orgasms, the cervix pushes down into the vagina.

Up to 50% of women expel various kinds of fluid from their urethra during sexual arousal or sexual intercourse. Studies have shown there are generally three types of fluid that are produced: urine, a dilute form of urine (known as “squirting”), and female ejaculate.

While some women may expel these fluids during arousal or sex, they are most commonly expelled during orgasm, and particularly through G-spot orgasm. So what is the difference between these fluids?

The release of urine during penetrative sex is usually as a result of stress urinary incontinence. Some women experience no other symptoms of stress urinary incontinence, such as leakage when sneezing, coughing or laughing, but will leak during sex.

“Squirting” is the leakage of a urine-like substance during orgasm. It is thought to occur because of strong muscle contractions surrounding the bladder during female orgasm.

Female ejaculate, most commonly reported with G-spot orgasm, is a much different substance: women describe the fluid as looking like watered-down fat-free milk and report producing about a teaspoon in volume during orgasm. The contents of female ejaculate have been chemically analysed and found that it closely resembles secretions from the male prostate. This has led to many suspecting that glands known as the female prostate (formerly Skene’s glands) produce this ejaculate.

What could the G-spot be?

The G-spot is not a single, distinct entity. Much debate exists in the research field as to just what the G-spot is, and how it can produce orgasm.

The G-spot is located in the clitourethrovaginal complex – the area where the clitoris, urethra and vagina all meet up. There are several structures in this complex that could produce pleasurable sensations when stimulated – the G-spot might reflect the stimulation of just one structure, or multiple structures at once. Two structures in particular have been hotly debated and stand out as likely candidates for producing G-spot orgasms: the female prostate and the clitoris.

The female prostate lies within the urethral sponge, a cushion of tissue surrounding the urethra. The urethral sponge and female prostate are highly innervated, which may explain their sensitivity when stimulated.

The clitoris is more than meets the eye: we now know this organ extends far beyond what is visible externally. Apart from where the urethra and vagina touch, the clitoris somewhat encircles the urethra. Mechanical stimulation of the G-spot may in fact be stimulating the internal portion of the clitoris.

So, is the G-spot fact or fiction?

The G-spot certainly exists in some women. However, not all women will find the stimulation of the G-spot pleasurable.

Just because a woman is not aroused when the G-area is stimulated, this does not mean she is in any way sexually dysfunctional. Sexuality and arousal have clear physiological and psychological links. But, as human beings, we are all made slightly anatomically and physiologically different.

In the same way that what I consider “blue” may not be the exact same “blue” you perceive, an orgasm in one woman is not the same as an orgasm in any other woman. It is a unique experience. And although you and I both see blue through our eyes, the complexities of human sexuality and the female reproductive organs mean women may achieve orgasm in multiple ways.

Some women are unable to orgasm in the presence of a partner, but have no difficulty with orgasm with masturbation. Some women can orgasm only with clitoral stimulation, while others can orgasm through vaginal stimulation alone. There are reports of women who experience orgasm through the stimulation of the foot, and Grafenberg detailed in his report women who experienced arousal through ear penile penetration (but these reports are yet to be replicated!).

You are not abnormal or strange or dysfunctional if you cannot find your G-spot. Similarly, you are not abnormal or strange or dysfunctional if you expel fluid during arousal or sex. Sexual arousal, desire and pleasure are individual: if you are unable to find your G-area, work on finding something that does fulfil your sexual needs.

Harry Potter star, feminist and all-round superstar Emma Watson supports a great website for women wanting to explore their sexuality further. It’s called OMGYes and is a great place to explore the ways in which different women experience sexual pleasure.

About The Author

Jane Chalmers, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, Western Sydney University. She is part of the Body in Mind Research Group at the University of South Australia. She is investigating neuroimmune responses in women with localised, provoked vestibulodynia.

Jane Chalmers, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, Western Sydney University. She is part of the Body in Mind Research Group at the University of South Australia. She is investigating neuroimmune responses in women with localised, provoked vestibulodynia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon