A new model could help make college students working together in teams feel more included, according to a new paper.

When Joel Geske, a professor in the Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University, asked his students a question about feeling left out from a team project or class discussion, a common theme emerged in their responses:

- “I felt left out due to personality difference… and I felt invisible.”

- “Felt like my opinion was not valued as much or I was expected to provide the black viewpoint.”

- “The teacher had people pick groups as if it were for a game in elementary school. Being one of the last picked, it made me feel very left out.”

- “I felt left out due to my age, being the oldest in the classroom when working in assigned groups there was little acknowledgment of my topics and very little interest in even interacting with me.”

The survey, designed to assess diversity and inclusion in the classroom, signaled a need for change. Geske helped conduct the survey when he was chair of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ diversity and inclusion committee.

While the survey was specific to the college, Geske says students in other colleges and even employees in the workplace would likely give similar responses. As he read the repeated comments of students feeling left out or not valued, it became clear instructors needed to focus on creating diverse teams that were also inclusive.

“Inclusion goes beyond diversity,” Geske says. “Diversity often focuses more on meeting a quota, but inclusion makes students feel they are part of the team or group and an actual contributor.”

Bringing more people in

Team projects are an integral part of the advertising courses Geske teaches to prepare students for the workplace. In a paper published in the Journal of Advertising Education, Geske outlined the models he adapted to create a more inclusive environment, particularly for teams working on semester-long ad campaigns or final projects.

He starts by having students privately fill out applications to identify their talents and skill sets as well as an optional section with demographic information. It’s a way for Geske to get to know the students so he can form teams with a diverse mix of skills as well as socioeconomic backgrounds, genders, races and ethnicities.

“Diversity doesn’t just happen by itself. You have to be intentional to be inclusive,” he says.

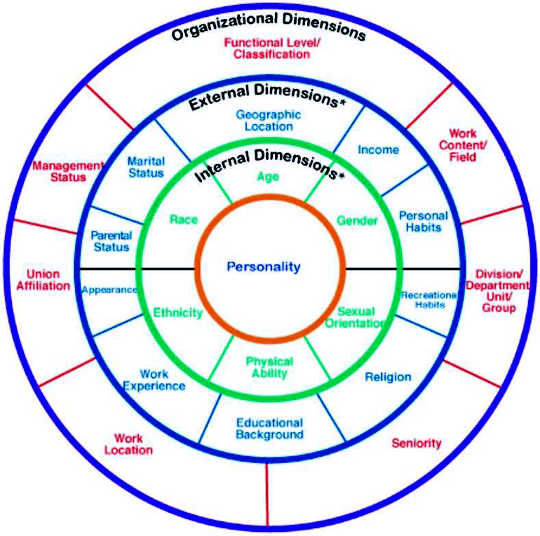

It is important for students to understand the purpose and benefit of what Geske is trying to achieve, which is why he assigns two readings: a Scientific American article (“How Diversity Makes Us Smarter”) and the Four Layers of Diversity model from the book Diverse Teams at Work (Society For Human Resource Management, 2003). The process is more time intensive than having students self-select or break into teams by number, but the outcomes are worth the extra effort, Geske says.

Geske uses this model from the book “Diverse Teams at Work” to create inclusive teams in the classroom. (Credit: Diverse Teams at Work)

Geske uses this model from the book “Diverse Teams at Work” to create inclusive teams in the classroom. (Credit: Diverse Teams at Work)

“The more viewpoints you bring to a team, the more creative the solutions,” Geske says. “It sounds kind of simplistic when you say it out loud, but in practice we don’t generally get this kind of diversity on teams.”

Different voices, better results

Geske uses an example in class of a Snickers ad that first aired during the 2007 Super Bowl and was later pulled after complaints it was homophobic. The ad shows two men doing a variety of “manly” activities after accidentally kissing while eating the candy bar. Geske says the ad makes the case for companies to build diverse work teams.

“Companies get into trouble when they don’t understand a culture or background. If the company had a gay person on that creative team, it never would have made that ad,” he says. “The more viewpoints involved at the beginning of the decision-making process lessens the likelihood of later offending some group of people.”

It is vital that the team environment allows for these different voices to be heard and respected, Geske adds. However, one individual should not be expected to speak for an entire gender, race or other demographic.

“An inclusive group recognizes that everybody has something to contribute and they’re not necessarily representative of an entire category,” Geske says. “You don’t call out people for their individual characteristics, but you value them for whatever they bring from their background and culture.”

Source: Iowa State University

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon