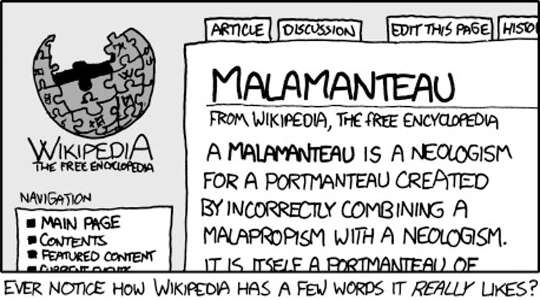

A ‘malamanteau’ is an extension of the malapropism. xkcd comics, CC BY-NC-SA

American film director Judd Apatow once confessed to Stephen Colbert that he’d been mispronouncing his wife Leslie Mann’s name for nearly two decades. He’d been saying “Lez-lee”, while she pronounces it as “Less-lee”. When he asked her why she hadn’t corrected his mistake, she said she “thought he wouldn’t be able to make the adjustment”. Barbra Streisand, unlike Mann, is reportedly insistent that her name be pronounced correctly by everyone, even Apple’s voice assistant Siri.

In Australia, mispronunciation is often said as “mispronounciation”. Although it is a noun, there’s no “noun” in it. In 1987, Harold Scruby, who later functioned as Deputy Mayor of the Mosman City Council, published a quirky compendium of instances of mispronunciation by Australians. He labelled these “Waynespeak”. Prior to the publication of Scruby’s book, his friend Leo Schofield had run some of the expressions in his Sydney Morning Herald column and been drowned in “a Niagara of correspondence”.

Hordes of respondents regarded these expressions to be at least non-standard, or just plain wrong. Despite this, many of Scruby’s examples remain current today: “anythink” and its companions “everythink”, “nothink”, and “somethink”; “arks” (“ask”); “astericks” (“asterisk”); “bought” (“brought”); “could of” (“could’ve”); “deteriate” (“deteriorate”); “ecksetra” (“et cetera”); “expresso” (“espresso”); “haitch” (“aitch”); “hone in” (“home in”); and so on through to the end of the alphabet with “youse”.

For those of us who wince we hear “youse”, it might be a surprise to find the term in a dictionary. The Macquarie Dictionary feels compelled to explain that the dictionary is a complete record of Australian English. The criterion for inclusion in it is thus “evidence of currency in the language community”.

When I polled friends for their pet pronunciation peeves, many of them listed those in the Waynespeak collection, while others added examples that readers may cringe at: “cachay” (“cache”) and “orientate” (“orient”).

A favourite was “Moët” – often pronounced as “Mo-eee” or “Mo-way”. The name is of Dutch origin and is correctly pronounced as “Mo-wett”. Moët drinkers (and customers of Nike, Hermes, Givenchy, Porsche, Adidas, Yves St Laurent, and Saucony) who wish to check whether they have been pronouncing their luxury products correctly can click on this advice.

My pet pronunciation peeve is the mispronunciation of the word “the” in front of a word beginning with a vowel. Many people, and just about all newsreaders, pronounce it as a neutral “thuh” instead of sounding it out as “thee”, as in “tea”. It’s thee apple, not thuh apple.

Mixed meanings

Some of the suggestions that surfaced in my poll classify as a “malapropism” rather than as a mispronunciation. The term “malapropism” derives from the name of a character in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s 1775 comedy of manners, The Rivals. Mrs Malaprop’s bungled attempts at erudite speech led her to declare one gentleman “the very pineapple of politeness!” and to say of another, “Illiterate him … from your memory”.

Writers of television scripts often create characters prone to malapropisms: Irene in Home and Away, Virginia Chance in Raising Hope, and Tony Soprano in The Sopranos. The Australian television characters Kath and Kim were notorious for their malapropisms, such as “I want to be effluent and practise serial monotony”.

Tony Abbott once embarrassingly substituted “suppository” for “repository”. In an article about the proposed airport at Badgerys Creek in Sydney, a reporter mentioned “a relatively modest and small group that would have some affectation”. Did the reporter mean “effect”?

The San Remo Hotel in San Francisco, meanwhile, highlights its “turn of the century decorum”. On the UK television show The Apprentice, one of the contestants talked about “appealing to the female genre”.

Other examples that I have noted include “What are you incinerating about me?”; “a Dorian of the theatre”; “a logo that amplifies modernism and professionalism”; “It’s not as if the English language is frozen in aspen” (though it’s pretty cold in Aspen); and “As we approach the footy finals, I can emphasise with the players”.

Justin Bieber once said: “I was detrimental to my own career”. I think we can guess that Justin meant “instrumental”, though he may have been just self-aware. We can also guess what the other malapropisms should have been (decor, gender, insinuating, doyen, exemplifies, aspic, empathise).

Note that there needs to be a tinge of humour for an expression or word to be labelled as a malapropism, and it needs to be a real word. Richard Lederer has a hugely amusing post on malapropisms on his Verbivore site, including this fine example: “If you wish to submit a recipe for publication in the cookbook, please include a short antidote concerning it”.

An extension of malapropism occurs in the malamanteau, which is a word that The Economist defines as an erroneous and unintentional portmanteau.

It was launched as a word on the xkcd comic strip and is apparently unpopular with the Wikipedia administration folks, who objected to the word having an entry on the site. The most quoted malamanteau is George W. Bush’s “I misunderestimated”. Others that have evoked smirks have been “miscommunicado” (from “miscommunicate” and “incommunicado”), “insinuendo” (from “innuendo” and “insinuation”), and “squirmish” (“squirm” and “skirmish”).

I recently heard a sparkling new malamanteau, “merticular”, used to describe a fussy person. It appears to combine “particular” and “meticulous”. When I questioned this and suggested that “meticulous” would do, the speaker said: “No. A merticular person functions at a higher level of "pickyness” than a “particular” person".

It’s over to you now: Are you merely “picky” or are you “merticular”?

Is it worthy of the moniker of malamanteau? If so, how would you spell it?

About The Author

Roslyn Petelin, Associate Professor in Writing, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Books by this Author:

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon