Research shows that trustworthiness involve three major attributes: Ability, integrity and dignity. (Shutterstock)

Research shows that trustworthiness involve three major attributes: Ability, integrity and dignity. (Shutterstock)

One of the topics most frequently discussed “at the water-cooler” is how much we may, or may not, trust people — from employers and managers to co-workers, friends and lovers.

Trust, of course, is vital for individual relationships and for organizational effectiveness — within universities and businesses alike. It creates an atmosphere where work is well-managed. It smooths the way, serving as a lubricant for an effective — and efficient — work environment.

We often think and talk about trust in abstract terms, using phrases such as “I like him” or “I trust her.” As an associate professor of education who has done research on trust, however, I have found trust is knowable.

We trust our bosses because they have the ability to do their job and to help us with our job. They are reliable, consistent and behave with integrity. And because they treat us, and others, with dignity.

These are the essential components of trusting relationships of all kinds — from work to family, friendships and romance. Trust can actually be calculated, and all bosses (and colleagues) will “score” in each area, at different rates.

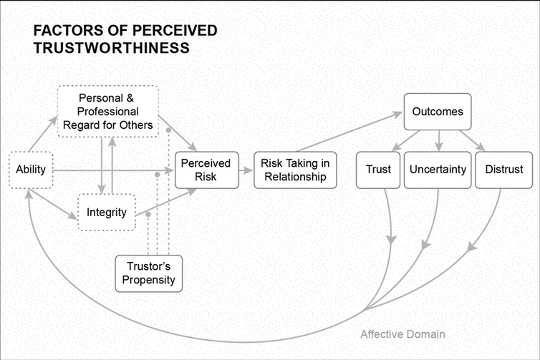

There are varying opinions about “how much” an individual behaviour matters in the establishment of trust. But much research indicates that details of trustworthiness involve three major attributes: ability, integrity and dignity.

Ability matters most

Ability comprises the first 50 per cent of this equation — it matters more than anything else. Ability relates to understanding the job, performing the job and helping others with their work-related issues in useful ways. It involves a general openness about what is required, what can be improved, and a willingness to perhaps co-design ways in which the work can be accomplished.

A person’s integrity is roughly 25 per cent of why we trust. Predictability and reliability are components of integrity. Other tightly related concepts include fairness and honesty. These must be phrased in the positive — we cannot be reliably unfair or regularly dishonest, for instance, and still gain another’s trust.

The construction of trust. Author provided

The construction of trust. Author provided

No one is perfect in these important areas, but a good boss will have created an environment in which, at the very least, they are recognized as trying to manage issues with the components essential to integrity.

Of course, openness, often thought of as a component of ability, helps us understand that integrity, on occasion, cannot always be revealed. Sometimes we must assume, based on a long series of other interactions, that a person is doing their level best, even if they cannot reveal the “why” of each exchange.

Vulnerability makes trust matter

The third part of the equation is treating others with dignity. This includes behaving in ways that are respectful and caring, as well as demonstrating loyalty, forgiveness and personal regard for others.

If bosses do this 25 per cent well, we are happy.

Willingness to take a risk is clearly an important component of organizational effectiveness, and is also closely connected to trust.

In fact, Oliver Williamson, winner of the 2009 Nobel prize in economics, identifies vulnerability as the key pre-existing element in why trust matters. If you aren’t vulnerable then trusting does not really matter.

We are all vulnerable at work. Our willingness to “make a difference” requires some careful, but essential, risk-taking.

So, “trusting our boss” means a great deal — to the individual relationship and to the organization. It might be time to deeply consider what we mean when we trust each other.![]()

About The Author

Victoria Handford, Associate Professor in Education, Thompson Rivers University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

{youtube}wtNOq1Bwtt4{/youtube}

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon