Gerry Koons, an MD/PhD student at Rice and Baylor College of Medicine, prepares a 3D-printed bioreactor for tests. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice)

A new technique grows live bone to repair craniofacial injuries by attaching a 3D-printed bioreactor—basically, a mold—to a rib.

Stem cells and blood vessels from the rib infiltrate scaffold material in the mold and replace it with natural bone custom-fit to the patient.

Bioengineer Antonios Mikos, a pioneer in the field of tissue engineering, and his colleagues combined technologies they have developed during a decade-long program. The goal is to advance craniofacial reconstruction by taking advantage of the body’s natural healing powers.

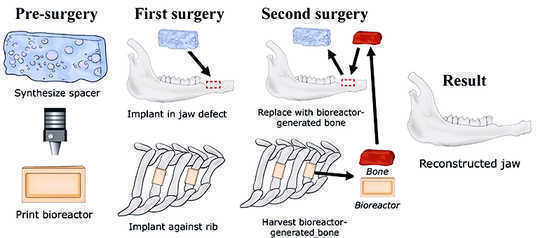

Researchers developed a technique to grow custom-fit bone implants to repair jawbone injuries from a patient’s own rib. (Credit: Mikos Research Group)

The technique is being developed to replace current reconstruction techniques that use bone graft tissues from different areas of a patient, such as the lower leg, hip, and shoulder.

Bone substitute

“A major innovation of this work is leveraging a 3D-printed bioreactor to form bone grown in another part of the body while we prime the defect to accept the newly generated tissue,” says Mikos, professor of bioengineering and chemical and biomolecular engineering at Rice University and a member of the National Academy of Engineering and National Academy of Medicine.

“Earlier studies established a technique for creating bone grafts with or without their own blood supply from real bone implanted into the chest cavity,” says coauthor Mark Wong, a professor, chair, and program director of the oral and maxillofacial surgery department with the School of Dentistry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

“This study demonstrated that we could create viable bone grafts from artificial bone substitute materials. The significant advantage of this approach is that you do not need to harvest a patient’s own bone to make a bone graft, but that other non-autogenous sources can be used,” he says.

Knitted and covered

To prove their concept, the researchers made a rectangular defect in the mandibles of sheep. They created a template for 3D printing and printed an implantable mold and a spacer, both made of PMMA, also known as bone cement. The goal of the spacer is to promote healing and prevent scar tissue from filling the defect site.

They removed enough bone from the animal model’s rib to expose the periosteum, which served as a source of stem cells and vasculature to seed scaffold material inside the mold. Test groups included crushed rib bone or synthetic calcium phosphate materials to make the biocompatible scaffold.

The mold, with the rib side open to create a tight interface, stayed in place for nine weeks before removal and transfer to the site of the defect, replacing the spacer. In the animal models, the new bone knitted to the old and soft tissue grew around and covered the site.

Why ribs?

“We chose to use ribs because they’re easily accessed and a rich source of stem cells and vessels, which infiltrate the scaffold and grow into new bone tissue that matches the patient,” Mikos says. “There’s no need for exogenous growth factors or cells that would complicate the regulatory approval process and translation to clinical applications.”

Ribs offer another advantage. “We can potentially grow new bone on multiple ribs at the same time,” says coauthor Gerry Koons, an MD/PhD student at Rice and Baylor College of Medicine currently working in Mikos’ lab.

Using PMMA for the mold and spacer was a simple decision, Mikos says, as it has been regulated as a medical device for biological applications for decades. In World War II, when fighter planes used PMMA windshields, doctors noticed that shards embedded in injured pilots did not cause inflammation and thus considered it benign. While the study’s initial goal is to improve the treatment of battlefield injuries, the big picture includes civilian surgeries as well.

The results appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

About the Authors

Additional coauthors are from Rice; the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; Baylor College of Medicine; Synthasome, Inc., San Diego; and Radboud University Medical Center, Netherlands.

The Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine funded the research. Additional support for the research came from the National Institutes of Health, the Osteo Science Foundation, the Barrow Scholars Program, and the Robert and Janice McNair Foundation.

Source: Rice University

books_science