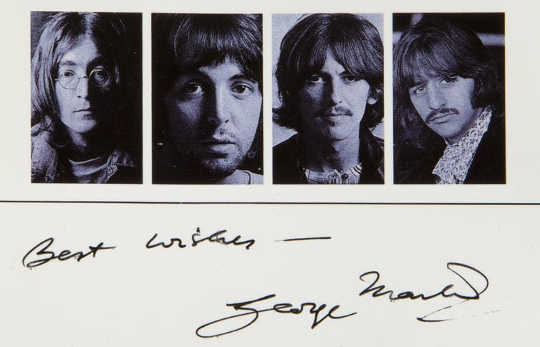

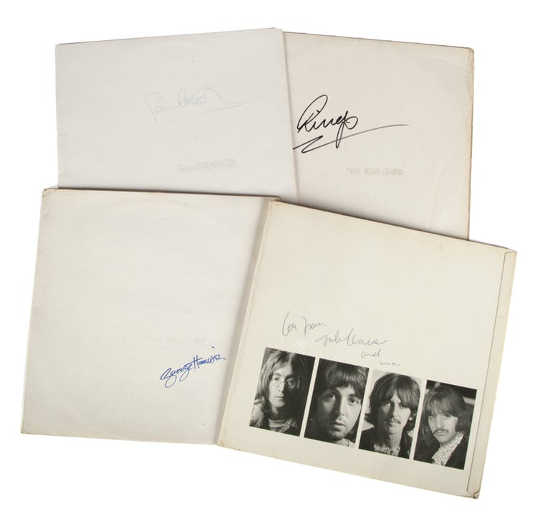

A copy of the original White Album signed by George Martin: his son Giles Martin and mix engineer Sam Okell have remixed the album on its 50th anniversary. Julien''s Auctions/Supplied by WE/AAP

Last year, in 2017, the 50th anniversary remix of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band gained considerable respect from critics and fans alike. Now we have the 50th anniversary remix of The Beatles, universally known as The White Album thanks to its ultra-minimalist artwork.

Before asking whether this remix achieves the same revelatory listening experience of its predecessor, it’s important to note a difference between the two albums. The original stereo mix of Sgt Pepper’s was long seen as inferior, mixed as it was when a mono mix was considered to be the definitive version of an album. By late 1968 that mindset had changed, and The White Album was the first Beatles album conceived primarily as a stereo album.

So is a remix even necessary? In certain genres of popular music, such as R & B, remixing is commonplace. In others, such as rock, it remains an ambiguous practice, especially when applied to classic albums—works which through reputation and repetition seem set in stone. For some fans, remixing a Beatles album is both artistically redundant and cynically commercial.

But remixing the Beatles is not new. Remixed Beatles songs can be heard on the album Let It Be, which was released in 1970, but started life as Get Back in 1969. When Get Back was shelved at the last minute, the session tapes were handed over to the producer Phil Spector — famous for his “wall of sound” aesthetic and currently serving a life sentence for murder — who “re-produced” the work in part by remixing a number of songs, infamously adding intrusive orchestral and choral parts in the process. Let it Be was subsequently reworked and remixed again, appearing (sans Spector’s additions) as Let it Be … Naked in 2003.

The White Album itself was the source of a creative remix when Danger Mouse (Brian Burton) did a mashup called The Grey Album (2004) that combined vocal performances from Jay-Z’s The Black Album with instrumental elements from The White Album. The album became a beacon for supporters of “remix culture”, a movement that supports the use of others’ intellectual property to create new work. The Beatles, perhaps inevitably, did not authorise Danger Mouse’s remix project. As Charles Fairchild writes, though, this project was “a link in a long chain of musical practice that stretches back to the late 1960s”.

The White Album — a sprawling, seemingly unfocused, 30-track double album — has had an odd reception. Long in the shadow of its predecessor, Sgt Pepper’s, its stocks have risen in the last two decades to the point where it is universally regarded as one of the Beatles’ greatest albums. So what does the 2018 remix — put together by producer Giles Martin (son of the album’s original producer, George Martin) and mix engineer Sam Okell — offer us?

The album has a more “modern” sound (wider frequency range, wider stereo field, and greater clarity and separation of parts), without losing its live feel, grit, or eccentricity. As the opener, Back in the USSR, shows, bass frequencies are considerably more present. (In the 1960s, mixing and mastering engineers had to be careful with low frequencies, as they could cause problems at the vinyl cutting stage.)

In addition to its more present low-end, and its (usually subtle) changes to the balance between instruments, the 2018 remix is most notable for adding detail and clarity. This last aspect is particularly welcome in the album’s closing track, John Lennon’s Good Night, with its shmaltzy strings-and-choir arrangement, a style that evoked (even then) an earlier cinematic era. Removing some of the heavy-handed reverb from the choir immediately makes the song clearer and more listenable.

More than anything, The White Album was a return to - and remixing of - rock’n’roll. Julien''s Auctions/Supplied by WE/AAP.

The first postmodern album?

While some might see this remix as a marketing exercise, it undoubtedly allows us to experience the album in a new way. It also draws attention to the “remix” aesthetic found within it.

Revolution 9, a piece of avant garde sound collage made up of found audio samples, is a fine example of early remix culture (an irony that was not lost on a number of Danger Mouses’s supporters). But The White Album engaged in “remix thinking” in less obvious ways. In its wild variety and use of pastiche, it has long been seen as the first postmodern album. Ranging from the mock-1920s style of Honey Pie, to the nursery-rhyme style of Cry Baby Cry, the album could be said to remix popular music itself.

More than anything, though, The White Album — coming in the wake of the Beatles’ psychedelic outputs of 1967 — was a return to, and remixing of, rock’n’roll. (In this respect, it prefigures the Get Back sessions in which the “back-to-roots” aesthetic became programmatic.) Starting as it does with a parody (by way of the Beach Boys) of Chuck Berry’s Back in the USA, The White Album repeatedly revises classic rock’n’roll tropes.

The remix of I’m So Tired makes the evocation of Berry’s guitar style (heard in the choruses) all the more apparent. Helter Skelter, with its use of tape echo and Elvis-esque vocal stylings from McCartney, is a reworking of 1950s rock’n’roll as much as an invention of heavy metal. Meanwhile, Revolution 1 and Happiness is a Warm Gun heavily rely on doo-wop vocals, a key style in the development of rock’n’roll.

This remix of the White Album is a less radical intervention in the Beatles’ canon than Love (a 2006 album of mashups) or Let it Be… Naked. And while it is less technically “necessary” and revelatory than the 2017 remix of Sgt Pepper’s, it gives us a clearer sonic view of the Beatles’ most eccentric and eclectic album.

Indeed, the Martin-Okell remix may well have given The White Album something that early critics of the record said it lacked: a degree of coherence.![]()

About The Author

David McCooey, Professor of Writing and Literature, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon