Manipulating environmental exposures to optimize a healthy microbiome may hold the promise of preventing chronic inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. (Shutterstock)

Manipulating environmental exposures to optimize a healthy microbiome may hold the promise of preventing chronic inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. (Shutterstock)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a mounting burden on health-care systems globally.

A 2012 study found that Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (two types of IBD) are significantly on the rise. A follow-up study published last year in The Lancet demonstrated that these diseases affect over 0.3 per cent of the population in North America, Oceania and many countries in Europe.

In Canada, the number of individuals affected by IBD is estimated to rise to around 0.7 per cent of the total population this year, and to almost a full percentage of the population (roughly 400,000 afflicted individuals) by 2030.

IBD was conservatively estimated to cost Canadians $2.8 billion per year in direct and indirect costs, as of 2012.

Like the horse charging at a steaming locomotive in Alex Colville’s 1954 painting, Horse and Train, our health-care system is on track to crash with the unstoppable force of IBD.

Unless, that is, we turn our head and aim for an opening.

This opening is “proactive medicine” — preventing the disease from occurring in the first place.

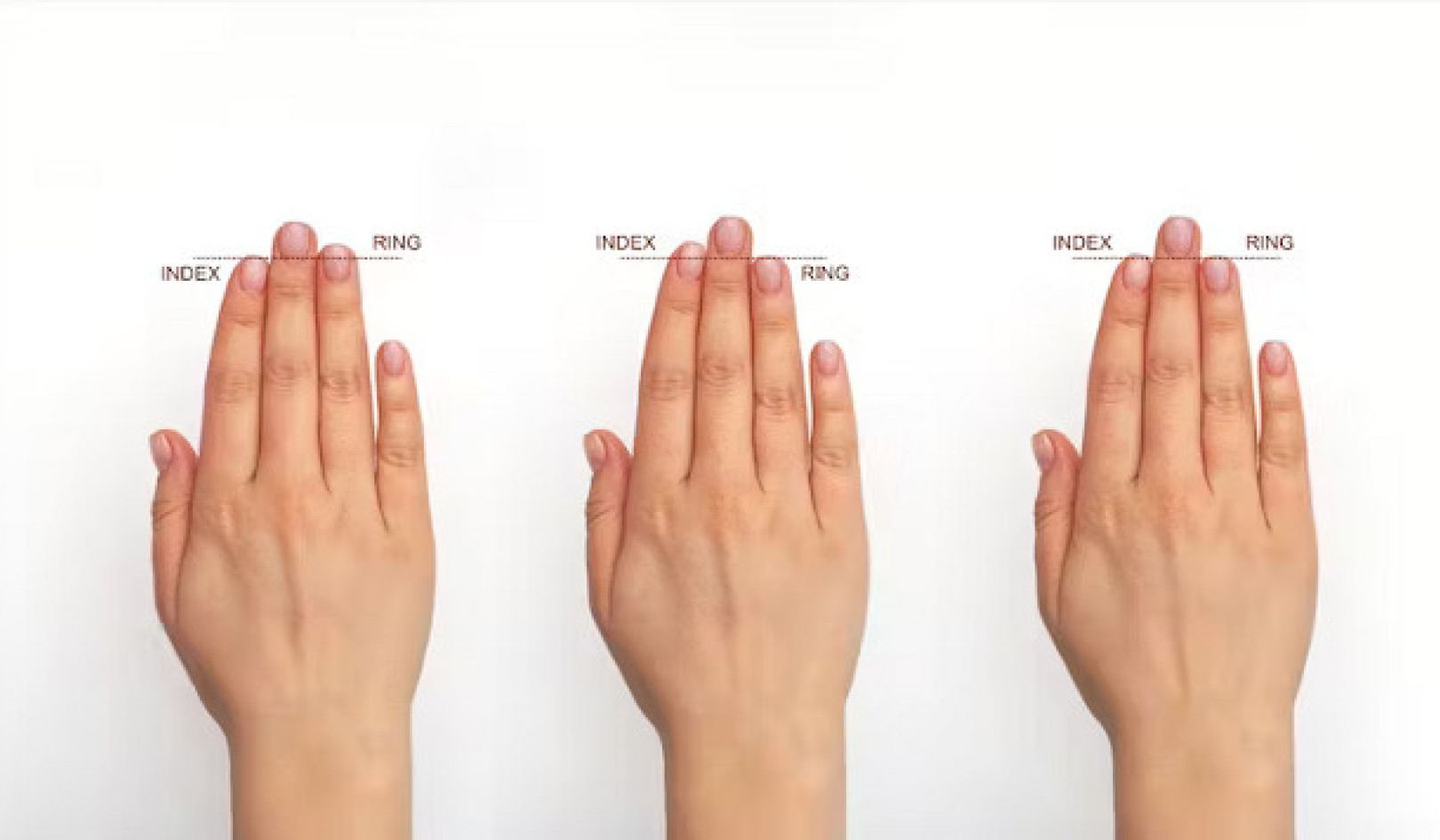

One way of achieving this may be to manipulate environmental exposures and optimize a healthy gut microbiome: The 100 trillion or so symbiotic microbes that live within our bodies that are necessary for our survival.

A chronic and incurable disease

Part of the reason for the dramatic increase in the number of individuals afflicted with IBD is because it is a disease of the young, most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 18 and 35.

IBD is a chronic and incurable disease with low mortality. Those diagnosed with IBD are not likely to die from the disease; they can live long lives. This combination of young age at diagnosis and low mortality leads to an epidemiologic concept called compounding prevalence.

We all know about compounding interest: If we start saving money in our 20s, over time and with a steady interest rate, our savings will experience compound growth. In our 60s, we will be left with a large sum of money for retirement.

Compounding prevalence, in contrast, is when new individuals are being added to the affected population (diagnosed with the disease) but existing cases are not being removed — leading to a steady rise in the number afflicted with disease.

A recent study forecasted that the prevalence of IBD will rise an average of three per cent per year over the next decade.

We are facing an impending disaster for our health-care systems, but one that may be averted by looking for solutions and altering our course now.

Smoking, diet and cleanliness

More often than not, clinicians are trained to practice reactive medicine: Treating a disease after it develops. For example, we treat Crohn’s disease with powerful, expensive, immune system suppressing medications; when these fail, we remove segments of the patients’ bowels.

Frequently, however, the disease returns, forcing us to continue this vicious cycle. The burgeoning number of patients with chronic inflammatory diseases who are being managed in a predominantly reactive health-care system has the potential to squeeze the system within an inch of its life — both in terms of fiscal and staffing resources.

We need to change the future of health care by starting to practice proactive medicine.

In order to prevent a disease, you have to understand the disease. In 2018, we have come to understand that chronic inflammatory diseases arise from interactions between susceptibility genes and environmental exposures linked to the Westernization of society, such as smoking, diet and even our intense focus on cleanliness.

Mutations in susceptibility genes can affect the interaction of the immune system and the gut microbiome. And this microbiome is set in early childhood where decisions such as bottle feeding or using antibiotics in infancy may raise the risk of developing IBD later in life.

Manipulating environmental exposures to optimize a healthy microbiome may hold the promise of preventing chronic inflammatory diseases. Examples can include breastfeeding, avoiding unnecessary antibiotics early in life and avoiding cigarettes.

We must prioritize proactive medicine

This is the critical moment at which we need a major investment from government, industry and the public to fund clinical and laboratory research to explain the origin of chronic inflammatory diseases and foster strategies for disease prevention.

Diseases like IBD have significantly increased in diagnoses and are already affecting millions of people in North America, and many more around the world.

Health-care systems must account for the exponential rise in cases of chronic inflammatory diseases or face an unstable system, overwhelmed by a flood of complex patients.

Averting this disaster requires a collective shift from clinicians, government and the public — towards supporting proactive medicine.

Prioritizing proactive medicine will mean funding research to create the best available evidence to develop recommendations around healthy living — from infancy to adulthood — to ultimately lower the number of people afflicted with chronic inflammatory diseases.

![]() By doing so, we may stand a chance at stemming the global rise of chronic diseases like IBD and avoid an ugly encounter with the proverbial train upon the tracks.

By doing so, we may stand a chance at stemming the global rise of chronic diseases like IBD and avoid an ugly encounter with the proverbial train upon the tracks.

About The Authors

Gilaad Kaplan, Associate Professor, Gastroenterology, University of Calgary; Joseph W. Windsor, Research Assistant, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, and Stephanie Coward, PhD Candidate in Epidemiology, University of Calgary

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon