Health care guidelines are produced in ever-increasing numbers. The National Guideline Clearinghouse, a U.S.-based public website compiling summaries of “clinical practice” (health care) guidelines, has over 1,000 entries and is updated weekly. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the U.K. has over 180 clinical guidelines. ![]()

Health care guidelines cover all aspects of medicine, from using aspirin to prevent heart attacks and colon cancer to managing earwax and caring for athletes with concussions.

Health care guidelines impact policy decisions and care for individuals. Recent research, though, suggests that the public has only a vague understanding of what guidelines are and how they are developed.

This is consistent with my own experience as a physician studying best practices for patient engagement in guideline development. Most of my patients and focus group participants are unfamiliar with how guidelines are developed. This can lead to uncertainty for patients and contributes to controversy, such as debates about mammography guidelines.

What are guidelines?

Before widespread internet access allowed people to search systematically for scientific evidence, “guidelines” often reflected suggestions from groups of experts on how to best manage – or prevent – a medical condition.

Current high-quality clinical practice guidelines, though, are anchored in a thorough review of available medical evidence.

This has led some organizations to revisit recommendations made in older guidelines less firmly based on medical evidence. Last year the Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services dropped recommendations for flossing of teeth from their dietary guidelines, though debate about this remains.

In this era of evidence-based medicine, various standards exist for developing clinical practice guidelines. These include standards from the Guidelines International Network and the U.S.-based Institute of Medicine. The Appraisal of Guidelines Research & Evaluation Enterprise (AGREE) publishes a tool to assess the quality and reporting of clinical practice guidelines.

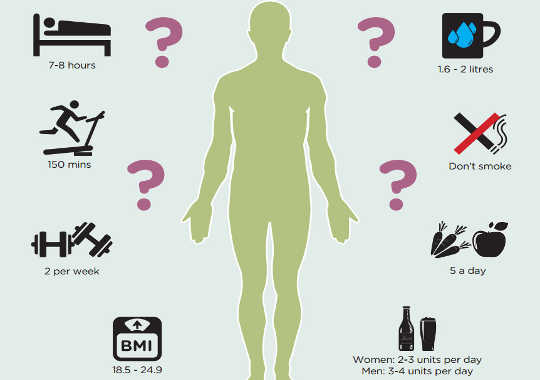

While different in some nuances, international standards agree on core elements. Guidelines summarize what is known (and not known) about different tests and treatments for health problems. They then make recommendations for expected best care, with specific descriptions of how confident guideline developers are in the research and recommendations.

High quality guidelines are developed by groups of patients and other public representatives, professional subject experts (physicians and other health professionals) and guideline specialists. These individuals decide what questions to ask, examine all the available research, grade the research quality, consider other issues (such as risks, benefits, availability, personal preferences and sometimes cost), and then make recommendations about best medical care.

Some guideline developers, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, seek public comment on plans for upcoming guidelines, draft evidence reviews, and recommendation statements to give the public a voice in the development process.

The reliance of guidelines on the best medical evidence means the recommendations are now less likely to be driven by panel members’ opinions and personal experiences. Practicing health professionals and the public can be more confident that recommendations are based largely on unbiased reviews of medical research and transparent weighing of benefits and harms.

Limitations

The term “clinical practice guideline” is reserved to describe “recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.”

However, some recommendations labeled (by developers or the media) as “guidelines” are actually policy or expert consensus statements provided without a full systematic review of medical research or offered in the absence of helpful studies. For example, recent screen time recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics are an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement rather than a formal clinical practice guideline.

Even when guidelines are based on systematic grading of the medical evidence, sometimes different developers make different recommendations. These conflicts are confusing for patients and for health professionals. Inconsistencies may reflect different approaches to panel composition, reviewing and grading medical evidence, interpretation of the evidence and/or weighing of risks and benefits. The inconsistencies may also represent more concerning possibilities such as contributions from conflicts of interest.

Putting guidelines to good use

A common misunderstanding about clinical practice guidelines is that they tell patients and health professionals what to do. Rather than identifying one “best” answer, clinical practice guidelines summarize what is known about medical options and describe anticipated benefits and risks. This information can then be used by patients and health professionals during shared decision making, which combines patients’ values and preferences alongside the best medical evidence to make an individualized decision.

Many clinical practice guidelines are now publicly available on websites. One resource for this is the National Guideline Clearinghouse, which accepts only guidelines meeting certain quality standards and which summarizes key elements of their development.

Understanding guideline debates can also inform decision making, helping patients and health professionals know when there is uncertainty in the field.

Every medical decision is a personal one, and rarely is there a single “right answer.” Trustworthy clinical practice guidelines are an important tool for improving the delivery of high quality health care to a broad audience. Individual decisions, though, are best made when patients partner with their health professionals to understand the evidence and incorporate their own medical history and values to make the best decision in that unique circumstance.

About The Author

Melissa J. Armstrong, Assistant Professor, Neurology, University of Florida

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon