Image by Gerd Altmann

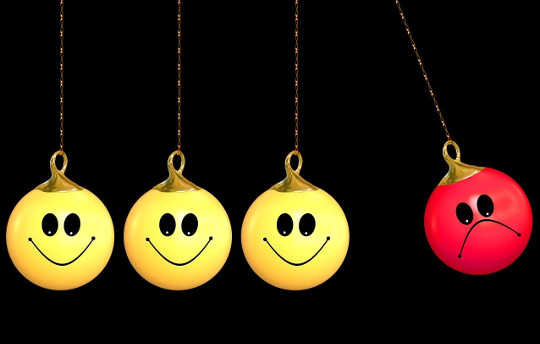

Our business personas are a special form of belief system. They are very real and solid to us and filled with myriad preconceptions about what is "right" and what is "wrong". When something occurs -- a criticism or a difference of opinion, for example -- that contradicts our preconceptions, we immediately react defensively. This defensiveness is the seed of conflict.

To make matters worse, this seed gets planted over and over again. The boss screams at you, so you scream at the first person who walks into your office, and that person in turn goes home and screams at their family. There's a harvest of conflict.

If your business persona always has to be right, any attempt to prove otherwise is likely to result in strong resistance. The more attached we are to our beliefs, the more solid and permanent they are, and the more likely we are to be engaged in conflict.

By examining your conflict patterns, you will begin to recognize that much of the anguish that you have put yourself through could have been avoided by relinquishing some of the solidity of your beliefs. This is not to say that you should now agree with everyone, whatever their opinions are, or that you should accept criticism without comment. Avoiding potential conflict situations, whatever the costs, can be as much an emotional pattern of clinging and rejection as any other. But a difference of opinion does not automatically need to become the grounds for conflict.

Learning to Prevent Conflict

There are three phases in every conflict: the beginning, when the potential for conflict first manifests; the middle, when conflict is in progress; and the end, when conflict is abating. Unless you're talking about invaders from Mars marching up the driveway unannounced, most people can see conflict coming long before it actually arrives. At least it should be possible to see conflict coming, if you're paying attention. The conditions for conflict build over time. Often it's simple basic likes and dislikes that become the seeds for conflict.

So your first task in working with conflict is to pay attention to your likes and dislikes and explore their potential for sparking conflict. You need to be aware that you have likes and dislikes and that they influence what you do, say, and think. It is not just your own likes and dislikes that you need to pay attention to. You also need to pay close attention to the preferences of those you work with.

There are two tools for accomplishing this. The first is to practice paying attention during daily activities. The second is your morning and evening contemplations. During the day, if you can calm your mind sufficiently, see the play of personalities in your work groups. Pay attention to what makes people happy, what makes people unhappy. In the morning and in the evening you should then be able to observe the impact of these preferences on your own feelings. Are there people who are beginning to irritate you? Is your work style beginning to irritate someone else? Is there someone you are beginning to dread talking to? Is someone avoiding talking to you? Why?

If you can maintain just a small amount of diligence in regard to paying attention and taking time for your daily contemplations, there is much which you can predict about the behavior of people -- who will work well together; who will fight; who will be leaders; who will prefer to be followers. There is a large body of literature and research about personality types and team dynamics to draw upon to support your observations. Without paying attention and your daily contemplations, however, be warned that all the one-day seminars and motivational speeches won't do much good.

Predicting how people will relate to each other is one thing; changing the outcome of situations is quite another.

Ending Conflict

The way you choose to resolve conflict speaks as much about you as the way a battle is fought. Many people are quite attached to conflict, liking the adrenaline rush, the sense of power -- especially if they win. They savor the memory. In some perverse way it makes them feel alive. For others, the experience is quite the opposite. The very thought of another conflict makes them sick to their stomachs. They will do anything rather than go through the experience again. Nothing is worth fighting for ever again. They will stay uninvolved from now on.

The way you choose to resolve conflict speaks as much about you as the way a battle is fought. Many people are quite attached to conflict, liking the adrenaline rush, the sense of power -- especially if they win. They savor the memory. In some perverse way it makes them feel alive. For others, the experience is quite the opposite. The very thought of another conflict makes them sick to their stomachs. They will do anything rather than go through the experience again. Nothing is worth fighting for ever again. They will stay uninvolved from now on.

Both extremes are just that -- extremes. In the first case, the adversary continues to be punished; in the second, it is the self that is punished. Punishment, however, has nothing to do with conflict. At the end of conflict, there is an antidote that should be foremost in the mind -- forgiveness. There are two people to forgive: the adversary and yourself.

Forgiving adversaries means dropping the conflict, both physically and mentally. Most people have heard the following Zen story, but it bears repeating. It is the story about the two Zen monks who approach a river. They will need to ford the river on foot. At the river bank there is a young woman who wants to get across but who doesn't want to get her dress wet. She asks the monks to carry her across. One of the monks gets angry and refuses. The second says nothing, picks up the woman, and carries her across. As the two monks continue their journey, the first monk who refused to carry the woman continues to fume about the insult. He complains to his companion, `"How could you do that? How could you carry that woman?" The second monk turns to his companion and smiles. "Are you still carrying her? I put her down back at the river."

Everyone is carrying young women, young men, two-ton gorillas, elephants, and heaven only knows what else on their shoulders. In working with conflict, we must learn when and how to put down the burdens. The burdens are the grudges, bad feelings, and resentments that result from conflict -- especially when you lose. Conflicts don't end when the last blow is struck. Even before the war is over, the next, bigger, stronger campaign is being plotted.

Conflict takes a lot of energy. A failure to forgive means being locked into a cycle of violence. And like the monk who couldn't put down the young woman in his mind, it means that energy will be expended in keeping the fight going. So conflict is expensive. In a practical sense it means that employees who spend all their time engaged in or plotting wars are not productive employees. They waste not only their time but the time of everyone around them in their personal battles.

Even when you blame yourself completely for it, conflict still takes a lot of energy. Self-blame, guilt, and rejection can be equally expensive of energy when pointed inward. One of the expenses when you blame yourself is the energy put into trying to make things right again. There has been a mistake and things need fixing, but even with superglue they will never be the same. Rather than going forward, a great deal of time is spent trying to fix the past. Trying to make things right again implies an unwillingness to accept your own fallibility and the fallibility of others. It is difficult to acknowledge that mistakes have been made.

The Sadness of Conflict

The sadness of conflict is that everyone has to live with its outcome. Conflict changes relationships. This has to be accepted. It is essential to the process of forgiveness. There are two techniques in particular that you can use after a conflict to help regain your emotional balance, forgive yourself and your adversaries, and get on with your life.

The sadness of conflict is that everyone has to live with its outcome. Conflict changes relationships. This has to be accepted. It is essential to the process of forgiveness. There are two techniques in particular that you can use after a conflict to help regain your emotional balance, forgive yourself and your adversaries, and get on with your life.

The first is a contemplation that you can do in the evening, or some other time when you want to work with it. Its theme is very simple and it goes like this:

We all want to be happy, each and everyone of us. What has just happened between ourselves and someone else is because of this. We wanted to be happy. Each of us, in our own way, tried to do what we thought was necessary to be happy.

If you feel now that it was you who was misguided, then you should try to feel some satisfaction that you had an opportunity to learn something that you didn't know about yourself. Perhaps now you have a better understanding of what makes you happy and what doesn't. You should ask yourself, "Is this something that I could have learned some other way? Is this maybe the only way that I could have learned this lesson?"

The same can be said of the lessons that your adversaries have learned. Even though they may have experienced a great deal of pain, was this best for them in the long run? Was it best for everyone involved?

If you can, make your thoughts toward others kind thoughts, based on the remembrance of your own struggles and the pain. Conflict is a shared experience of pain. Use it as an opportunity to develop your empathy for others.

When conflict is not positively resolved for everyone concerned, your feelings should be those of regret and compassion. Your adversary may not have learned valuable lessons; perhaps you have not learned lessons as well. In this case, you are both likely to repeat the same patterns of misery over and over again. It is not a very happy thought. Not something to rejoice about.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher,

Park Street Press, a div. of Inner Traditions Intl.

©1999. http://innertraditions.com

Article Source

Enlightened Management: Bringing Buddhist Principles to Work

by Dona Witten and Akong Tulku Rinpoche.

By applying Buddhist principles to the workplace the authors provide new insights into the true meaning of responsibility and the importance of focus. They teach how to relax under pressure and control emotions, and provide tips on constructive conflict resolution and understanding personal limits. More than just a book on achieving success, Enlightened Management is about creating happiness for all involved, employer as well as employee. Packed with exercises and techniques, Enlightened Management shows how to draw the best out of ourselves and our colleagues to create the productive, balanced, and happy office environment in which everyone dreams of working.

By applying Buddhist principles to the workplace the authors provide new insights into the true meaning of responsibility and the importance of focus. They teach how to relax under pressure and control emotions, and provide tips on constructive conflict resolution and understanding personal limits. More than just a book on achieving success, Enlightened Management is about creating happiness for all involved, employer as well as employee. Packed with exercises and techniques, Enlightened Management shows how to draw the best out of ourselves and our colleagues to create the productive, balanced, and happy office environment in which everyone dreams of working.

About The Authors

AKONG TULKU RINPOCHE was the president of ROKPA, an international relief organization. Visit ROKPA's website at http://rokpa.org. The author of Taming the Tiger, he was the founder and director of Samye Ling in Scotland, the oldest Tibetan Buddhist center in the West. Visit the Center's website at http://www.samyeling.org.

AKONG TULKU RINPOCHE was the president of ROKPA, an international relief organization. Visit ROKPA's website at http://rokpa.org. The author of Taming the Tiger, he was the founder and director of Samye Ling in Scotland, the oldest Tibetan Buddhist center in the West. Visit the Center's website at http://www.samyeling.org.

DONA WITTEN is a management consultant for Ernst and Young and has served in similar roles for major companies such as IBM and Cadbury.