Hukou Waterfall of Yellow River, China. Leruswing /Wikimedia , CC BY-SA

A good news story about China’s environment is something you don’t hear every day. But a major review published today in Nature has found that China has made significant progress in battling the environmental catastrophes of the past century.

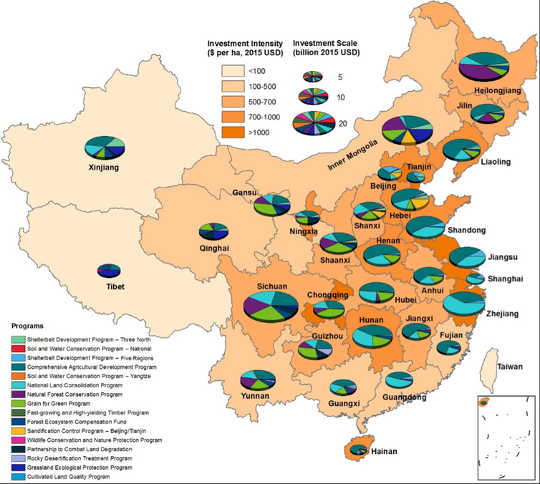

Our team, which included 19 scientists from 16 Australian, Chinese and US institutions, reviewed China’s 16 major programs designed to improve the sustainability of its rural environment and people.

We wanted to tell the story of China’s progress, so that other nations may learn from its experience as they strive towards the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

A monumental effort

From 1998, China dramatically escalated its investment in rural sustainability. Through to 2015, more than US$350 billion was invested in 16 sustainability programs, addressing more than 620 million hectares (65% of China’s land area).

This effort, while imperfect, is globally unrivalled. Its environmental objectives included:

- reducing erosion, sedimentation, and flooding in the Yangtze and Yellow rivers

- conserving forests in the north-east

- mitigating desertification in the dry north and rocky south

- reducing the impact of dust storms on the capital Beijing

- increasing agricultural productivity in China’s centre and east.

Just as important were the socio-economic objectives of poverty reduction and economic development, particularly in western China.

Programs improved livelihoods by paying farmers to implement sustainability measures on their land. Providing housing and off-farm work in China’s booming cities also boosted household incomes and reduced pressure on land.

Click to enlarge: Investment under the 16 sustainability programs across China’s provinces from 1978 to 2015. Author provided

Click to enlarge: Investment under the 16 sustainability programs across China’s provinces from 1978 to 2015. Author provided

An environmental emergency

China’s pivot towards sustainability in the late 1990s came as a type of emergency response to the heinous condition of its rural people and environment.

China has been farmed for more than 8,000 years, but by the mid-1900s the cumulative impacts of inefficient and unsustainable agricultural practices and the over-exploitation of natural resources caused widespread poverty and environmental degradation.

Floods, droughts, and other catastrophes ensued, including the Great Chinese Famine from 1959-61, which caused between 20 million and 45 million deaths.

{youtube}ojOmUWLDG18{/youtube}

Following the 1978 economic reforms, six sustainability programs were established, but with only modest investment conditions continued to deteriorate. By the 1990s natural forest cover was below 10% and around 5 billion tonnes of soil eroded annually, causing major water quality and sedimentation problems.

In the Loess Plateau, the worst-affected parts were losing 100 tonnes of soil per hectare each year to erosion, and the Yellow River that flowed through it had the dubious honour of being the world’s muddiest waterway.

Agricultural soils were exhausted and productivity was down, grasslands were overgrazed, and more than a quarter of China was desertified.

In the late 1990s, China experienced a series of natural disasters widely believed to have been caused by unsustainable land management, including the Yellow River drought in 1997, the Yangtze River floods in 1998, and the severe dust storms that repeatedly afflicted Beijing in 2000.

This sustainability emergency triggered a great acceleration in investment after 1998, including the launch of 11 new programs. The portfolio included iconic programs such as the Grain for Green Program, the Natural Forest Conservation Program, and the Three North Shelterbelt Program which aimed to slow and reverse desertification by planting a 4,500km Great Green Wall.

{youtube}xgXKNJNP_ZQ{/youtube}

The result

After 20 years the results of these programs have been overwhelmingly positive. Deforestation has declined and forest cover has exceeded 22%. Grasslands have expanded and regenerated. Desertification trends have reversed in many areas, and while mostly driven by climatic change, restoration efforts have helped.

Soil erosion has waned substantially and water quality and river sedimentation have improved dramatically. Yellow River sediment loads have fallen by 90% and the Yangtze is not far behind. Agricultural productivity has increased through efficiency gains and technological advances. Rural households are generally better off and hunger has largely disappeared.

That said, there have also been significant unintended consequences. Afforestation – or planting trees where trees never grew – has dried up water resources and led to high rates of plantation failure.

In the most degraded areas, significant cultural disruption has occurred through the migration of entire communities to less sensitive environments. More could be done to conserve biodiversity, particularly by prioritising diverse natural forest restoration and regeneration over single-species plantations.

The precise impacts of China’s sustainability programs are clouded by other influences such as the One Child Policy and Household Responsibility System, urbanisation and development, and environmental change. Detailed and comprehensive evaluations are now needed to disentangle these factors.

Lessons from China’s experience

While the context of China’s path to sustainability is unique, other countries can learn from its experience. Nations must commit to sustainability as a long-term, large-scale public investment like education, health, defence, and infrastructure.

We do not wish to pretend that China is a global poster child of sustainability. Very serious pollution of its air, water, and soils, urban expansion, vanishing coastal wetlands and the illegal wildlife trade still dog the world’s most populous nation.

As China cleans up its domestic environment, great care needs to be taken not to simply shift problems offshore.

But to give credit where credit is due, China’s vast investment has made great strides towards improving the sustainability of rural people and nature.

![]() China’s path towards sustainability is clearly charted in the 13th Five Year Plan where President Xi’s Chinese dream for an ecological civilization and a “beautiful China” is laid out.

China’s path towards sustainability is clearly charted in the 13th Five Year Plan where President Xi’s Chinese dream for an ecological civilization and a “beautiful China” is laid out.

About The Author

Brett Bryan, Professor of Global Change, Environment, and Society, Deakin University and Lei Gao, Senior Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon