The United States is home to some of the most creative people and businesses on the planet. Our filmmakers, artists, software engineers and scientists entertain the world and expand the boundaries of human knowledge. Their creative process is often a mystery, but their tools are not. Among these tools, few are more critical than the internet, which fosters creativity and innovation by facilitating access to information and supporting collaborative work. It is the enzyme that accelerates the creative economy, much like waterways, railroads and roads fueled the industrial era. ![]()

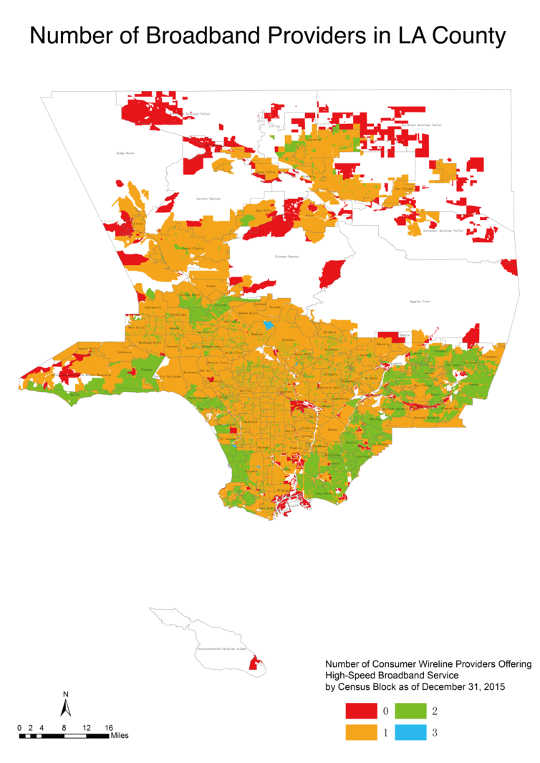

But there is a catch: Our world-class creators live in communities where internet access services are far from world-class. Take the example of Los Angeles, a major creativity hub: Using data from the California Public Utilities Commission, we mapped the availability of different home internet services across Los Angeles County. We then combined the results with demographic data, which allowed us to analyze the interplay between internet infrastructure and community demographics in close geographical detail.

Our results show that nearly two-thirds of Angelenos live in areas served by just one internet provider that offers speeds meeting the Federal Communications Commission’s current definition of “broadband” service – 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload. Competition is slightly stronger in the wealthier areas of the county, along the coast and in the San Fernando Valley.

Only one-third of Los Angeles County residents have more than one option for internet service that meets the FCC’s broadband standard. Hernán Galperin, CC BY-ND

Only one-third of Los Angeles County residents have more than one option for internet service that meets the FCC’s broadband standard. Hernán Galperin, CC BY-ND

Weak competition yields high prices for consumers and little pressure for companies to upgrade their networks to offer better service. For example, in LA County, fiber-based services (capable of delivering speeds far faster than legacy technologies like cable or DSL) are available in less than a quarter of census blocks. By comparison, fiber coverage in cities like Stockholm and Paris (where residents have a choice of at least six providers) is approaching 100 percent. Further, the speeds offered in monopoly areas are 35 percent lower than those offered in areas with three or more competitors. This suggests that increasing competition in America’s broadband market would offer a better on-ramp to the creative lifeline of the internet.

Little head-to-head competition

The situation in LA County reflects two major trends in U.S. broadband markets:

1) The ongoing industry consolidation in the telecom and cable TV markets;

2) Weak competition between DSL (which uses existing landline telephone wires to deliver broadband) and cable-internet services.

One of our key findings is that there is almost no geographical overlap between competitors with the same technology. Of the more than 73,000 census blocks in LA County – the smallest unit of geography government data can be broken into – only about 2,500 (3 percent) are served by more than one DSL provider. Likewise, only 850 blocks (about 1 percent) are served by more than one cable-internet provider. Alas, most households have to choose between one cable provider and one DSL provider; often, one of them fails to meet the FCC’s broadband speed threshold.

Competition has reached such lows that recent mergers aren’t making much difference. Take, for example, Charter Communications’ acquisition of Time Warner Cable in May 2016, a mega-merger of cable rivals that was expected to reduce competition and increase prices throughout LA County. But fewer than 1 percent of Angelenos lived in areas previously served by both operators. The merger couldn’t reduce competition because there was so little tto begin with, as companies divvy up territory to avoid competition.

The most recent FCC Broadband Report finds that the situation in Los Angeles is typical of other large metro areas. And it is worse in rural America, where 40 percent of residents lack access to broadband services.

Communities stand up for themselves

A key barrier to more competition is the expense of installing wired networks across large areas. In the past, federal policies required the few companies with existing networks to allow competing providers to serve customers over those same wires. But those days are gone, largely because the incumbent cable and phone companies successfully fought them in court.

As a result, many local governments have taken matters into their own hands. In 2014, LA Mayor Eric Garcetti launched CityLinkLA seeking to secure private investments in high-speed internet networks that would provide every resident with a basic level of internet service for free, or at very low cost. The system Garcetti envisioned would also be able to offer much faster speeds than today’s commercial service – 1 Gbps or more – at competitive rates.

So far, however, CityLinkLA has not attracted large investments in new broadband infrastructure, particularly for gigabit-speed services. Moreover, our analysis shows that fiber-optic investments have been concentrated in wealthier communities, exacerbating the growing divide between those with lightning-speed home connections and a digital underclass forced to rely on their smartphones and mobile data plans.

Geography and demographics present numerous challenges to the roll-out of advanced network infrastructure in many U.S. cities, including Los Angeles. However, an analysis by the Center for Public Integrity shows that, when comparing US and French cities with similar population densities (such as Nice and Columbus, OH), Americans paid more and had less choice in broadband. If our people and businesses are to continue thriving in a knowledge-based economy, and if we seek to build new opportunities for struggling communities, we must do better.

Help is unlikely to come from Washington, where the newly appointed FCC chairman has consistently voted against federal subsidies for broadband expansion projects. Rather, we should look at the example of communities across America, large and small, that are building upon existing city assets to accelerate the equitable deployment of next-generation internet infrastructure. For example, the city of Los Angeles already owns over 800 miles of fiber optic cable, and there is significant spare capacity. This and other locally owned assets can be leveraged to offer Angelenos, and Americans, the world-class internet service they deserve.

About The Authors

Hernán Galperin, Research Associate Professor of Communication, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism; Annette M. Kim, Associate Professor of Public Policy, University of Southern California, and François Bar, Professor of Communication and Spatial Sciences, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon