President Donald Trump at the Tulsa campaign rally, where he said he had slowed down COVID-19 testing to keep the numbers low. Win McNamee/Getty Images

President Donald Trump at the Tulsa campaign rally, where he said he had slowed down COVID-19 testing to keep the numbers low. Win McNamee/Getty Images

During a recent Senate committee hearing on the COVID-19 crisis, Dr. Anthony Fauci told lawmakers he was concerned about “a lack of trust of authority, a lack of trust in government.”

He had reason to be worried. The Pew Center reported that July 7 only 17% of people in the U.S. have confidence in government to do the right thing. Never in the history of their surveys, which began in 1958, has that confidence been so low.

Why is trust so low and why does that matter, especially during a crisis – and especially during this crisis?

No playbook

The dilemma of leadership in modern democracy has long been the focus of my scholarship and teaching. I have asked what qualities and virtues leaders need to preside over a government of, by and for the people. If it’s a challenging topic, it is also one never lacking for material. The current era points especially to the importance of trust for effective and legitimate leadership in democracies.

The story begins with a basic principle of democracy: Leaders cannot do whatever they please.

The drafters of the United States Constitution assumed that anyone with power would always have the opportunity – and often the temptation – to abuse it. To protect society from unruly rulers, they set up an obstacle course of elaborate procedures, checks and balances, separated powers and a stringent rule of law that applied to everyone, even those who wrote the laws.

In this system, inefficiency and complexity became virtues. Deliberation trumped dispatch.

It isn’t easy for leaders to act, and it is not supposed to be.

That’s a problem during a crisis. Emergencies require swift, decisive steps, sometimes improvised and often pushing the boundaries of formal authority.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

There’s no playbook, and those hurdles designed to prevent leaders from doing bad things may now prevent them from doing necessary things.

Even John Locke, the 17th-century British philosopher so influential in the American approach to accountability and limited government, understood that stuff happens. And when it does, the machinery of government may prove too slow and cumbersome.

With regret but cold realism, Locke conceded that when severe threats appear, “There is a latitude left to the executive power, to do many things of choice which the laws do not prescribe.”

Discretion granted, trust needed

German leader Angela Merkel’s cool, measured and rational approach inspires confidence. John MacDougall/AFP via Getty Images

German leader Angela Merkel’s cool, measured and rational approach inspires confidence. John MacDougall/AFP via Getty Images

That’s precisely when trust becomes critical.

The discretion granted to democratic leaders in times of crisis – the room they have to maneuver – depends entirely on how much the people trust them. And that depends on their competency, honesty and commitment to the public interest.

One of Dwight Eisenhower’s biographers explains that discipline was central to his leadership style. Eisenhower leaned heavily on experts and had the patience and persistence to navigate the complex machinery of government. Sometimes that made him appear cautious, but few questioned his competence.

Today German Chancellor Angela Merkel embodies the same set of skills, a cool, measured and rational approach that inspires confidence. High among her leadership qualities is a projection of competence, no doubt enhanced by Germany’s success responding to the pandemic.

The Financial Times political columnist Gideon Rachman wonders if the pandemic will ultimately be a setback for populist leaders such as Boris Johnson in Great Britain, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the United States. They seem thrilled by the theater of politics but bored by the details of governing. As their countries suffer some of the worst effects of the pandemic, Rachman believes citizens will rediscover the value of sheer competence.

Honesty and the public interest

Telling the truth also earns trust.

But honesty is more than just conveying basic facts. It is the capacity to explain the crisis, the sacrifice required and the path to a solution.

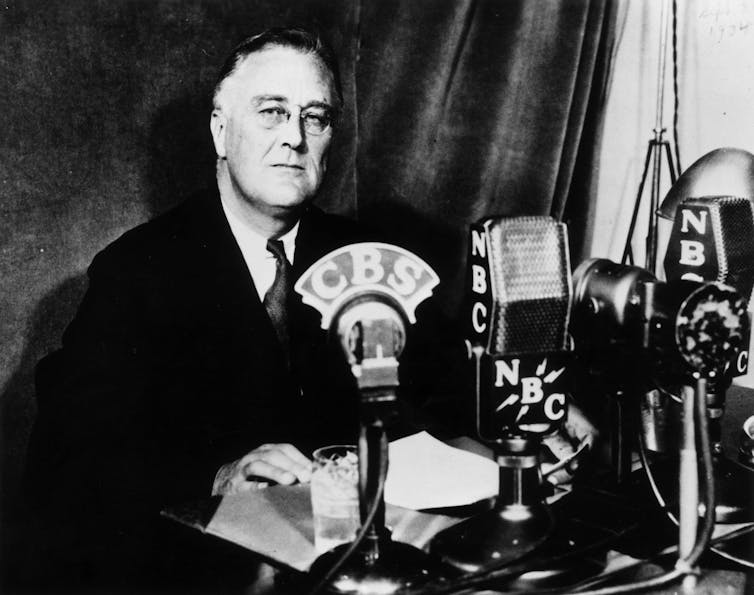

During his ‘fireside chats,’ President Franklin Roosevelt’s calm, clear and accessible explanations about the challenges of the Depression were instrumental in reassuring the nation. MPI/Getty images

During his ‘fireside chats,’ President Franklin Roosevelt’s calm, clear and accessible explanations about the challenges of the Depression were instrumental in reassuring the nation. MPI/Getty images

Roosevelt during the Depression, Churchill during World War II, Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis and Bush in the aftermath of 9/11 (at least the immediate aftermath) were granted considerable discretion because they accurately described and credibly interpreted the challenge facing the people.

In the current crisis, medical professionals have told the inconvenient truths about the pandemic. Political leaders at the national level have offered false hopes and misleading information. That is why trust in medical professionals in the United States far exceeds trust in elected officials.

Finally, trust is given when leaders act in the public interest, not their own self-interest.

Perhaps the most damning indictment in John Bolton’s book about his time in the Trump administration was this assessment of the president: “I am hard-pressed to identify a significant Trump decision during my tenure that wasn’t driven by reelection calculations.”

One 2016 Trump voter explained his recent change of heart even more bluntly: “It was like this dude is just in it for himself. I thought he was supposed to be for the people.”

If that perception becomes widespread, it will deplete whatever stock of trust citizens have left for the president. Those Pew measures of trust are fundamental expressions of whether citizens believe leaders will forsake their own immediate interests to serve a public interest.

Dr. Fauci is right. A solution to the pandemic requires testing, contact tracing, masks, social distancing and ultimately a vaccine. It also requires leaders who are competent, honest and committed to the public interest – leaders who are trustworthy.

The absence of trust jeopardizes an effective response to a health crisis. But it also creates a political crisis, a loss of faith in democracy as a way to govern ourselves. Public health in the U.S. is at stake. So is the health of democracy.![]()

About The Author

Kenneth P. Ruscio, Senior Distinguished Lecturer, Jepson School of Leadership Studies, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books:

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century

by Timothy Snyder

This book offers lessons from history for preserving and defending democracy, including the importance of institutions, the role of individual citizens, and the dangers of authoritarianism.

Click for more info or to order

Our Time Is Now: Power, Purpose, and the Fight for a Fair America

by Stacey Abrams

The author, a politician and activist, shares her vision for a more inclusive and just democracy and offers practical strategies for political engagement and voter mobilization.

Click for more info or to order

How Democracies Die

by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt

This book examines the warning signs and causes of democratic breakdown, drawing on case studies from around the world to offer insights into how to safeguard democracy.

Click for more info or to order

The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism

by Thomas Frank

The author offers a history of populist movements in the United States and critiques the "anti-populist" ideology that he argues has stifled democratic reform and progress.

Click for more info or to order

Democracy in One Book or Less: How It Works, Why It Doesn't, and Why Fixing It Is Easier Than You Think

by David Litt

This book offers an overview of democracy, including its strengths and weaknesses, and proposes reforms to make the system more responsive and accountable.