The wasteland in The Quest for the Holy Grail is a metaphor for our state of being when we're not living our lives from our hearts. When the Knight Parsifal, who is seeking the Grail, first encounters the wounded king of the wasteland, he's moved by compassion and wants to ask the monarch why he's suffering. But, having been trained that knights don't ask unnecessary and intrusive questions, he stifles his spontaneity and compassion and at this point his quest fails. It takes him an additional five years of struggle and failure to make his way back to the Grail Castle and to ask the questions that come from his heart rather than follow the rules of decorum for knights. Knowing the right questions reflects the maturity Parsifal has gained through the committed struggles of his quest and begins the healing of the wasteland.

It is a paradox that if we cannot open our hearts to ourselves then we have no foundation for dealing with other people lovingly and compassionately. And, like Parsifal we've been trained not to ask loving and compassionate questions of ourselves, not to question our depressions and heart attacks deeply and lovingly because to do so might upset the value systems we and our society live by. Instead, the system teaches us to go to the refrigerator, buy something, go to the movies, or out to eat if we are feeling lonely, anxious, or distressed. But feeling bad and going to the kitchen sets up a cycle that cannot be eased or healed by diet plans, willpower, or medication. Our real needs are deeper than what these palliatives can help. We have to pay better attention to ourselves.

Yes, in spite of our interests in exercise, fitness, and nutrition we still deny many of our bodies' needs. We work out to improve them, but too often we are treating the body like an "it" rather than the seat of our souls. We judge our bodies harshly against media ideals and frequently seem to disassociate from them. We rarely give them enough sleep, rest, and sensual rewards to keep them calm and relaxed, and sooner or later our bodies teach us we're human. Heart attacks, depression, obesity, chronic fatigue, and fibromyalgia are but a few of the ways our bodies do this and insist that attention be paid.

Betrayal or Warning?

In many of these circumstances we act as if our bodies have betrayed us, when actually they are more often our friends warning us when we are endangering ourselves. For instance our bodies know when we've inadvisably ingested bad or tainted food and reflectively expels what it must. Similarly our bodies issue "warnings" in the form of scares, those small reality episodes that are meant to wake us up to the changes we need to make. And, sometimes our bodies give us important signals about our emotions when we're hungry for love, personal fulfillment, or vitality.

I still remember how difficult it was for me as a child to figure out what kind of present to give my father for his birthday or Christmas. I could never figure out anything he needed or wanted and he never voiced a tangible desire. Even when I'd ask him directly he would answer something along the lines of "Whatever you would like to get." The broader emotional undertone of this simple-sounding answer can actually be quite frightening. If someone doesn't want or need anything from us how can we feel important to them?

This was a theme that remained throughout my relationship with my father. I thought he loved me but I could never figure out why I was important to him, what value I offered to his life. If we aren't aware of our needs and desires, if we hide them, it makes it very difficult for people to feel close to us for we've positioned ourselves as islands in life.

Understanding Our Needs

The fairy tale "The Fisherman's Wife" reminds me of a different danger that can arise when we don't genuinely understand our needs. In this story a poor fisherman who lives with his wife in a humble pigsty is fishing. The day wears on without his having any luck until close to evening he finally hooks a flounder. To his surprise the flounder begins to speak to him. The flounder tells a sad tale of being an enchanted prince. Filled with compassion the fisherman returns him to the sea and goes home empty handed. At home he relates his adventure to his wife. She becomes upset and urges him to go back to the sea and ask the flounder to grant him a wish. Early the next morning he returns to the sea and asks the fish to grant him a wish, a new cottage, for him and his wife. Home again, he finds that his wish has been granted and his wife is standing in front of a lovely cottage. Enthused, the wife continues pushing her husband to ask for a new favor day after day. They progress from a cottage to a house, a mansion, a castle, and then a marble palace. Finally the disgusted flounder has had enough and returns them to the pigsty. Like the fisherman's wife, if we don't understand our needs we too can get caught on a treadmill of acquiring material possessions that eventually leave us as emotionally or spiritually impoverished as we were when we began our quest.

The hurried pace of our lives discourages us from actively reflecting upon our needs and looking deeper than the material level. When we fail to understand them for ourselves and to share them, we cannot live from our hearts. The point here is that we then live by other people's concepts, calculations, assumptions, or inclinations -- right for them but maybe not for us. By probing our own inner lives, we give our relationships a better chance to succeed. Intimacy is about sharing. It is reciprocal. And when we relinquish or lose touch with our heart's desire, we leave ourselves in danger of being dissatisfied with life without realizing why.

Cultivating our self-awareness frequently helps us discover parts of our lives we're missing. For many years I made the same mistake with my children my father had made with me. Through my inner work I've learned to let them know I want and need things from them that go far beyond obligatory gifts and include their love, value to my life, and the meaning it gives me to be a father. As a result our exchanges of presents have become meaningful rather than obligatory because they symbolize this deeper exchange.

Not long ago I was asked to give a class on some of the topics we've been discussing at a local church. When I asked the people in the class to think about why it's important to be carefully aware of our needs and what we might be missing if we aren't, they found these questions initially difficult. Maybe they found these questions more troubling because we were in a religious setting. On the one hand our religious institutions generally try to teach us to think of other people and not ourselves. On the other hand our culture teaches us we should think of ourselves on a material level. I then broke the class members into small groups and had them look at these questions, and talk about them for a while. When we all reassembled as one group, sharing our answers, I was pleased by their thoughtful responses:

* We can't know ourselves if we don't know what we need.

* Our real needs can show us what our lives are about.

* If we don't know our needs, no one else can really know us.

* If we don't know our needs, they are unlikely to get met.

* If we don't know our needs, we'll expect other people to know them.

* If we don't know our needs, we may become more demanding than we realize.

* If we don't know our needs, we'll live like sheep.

* Being aware of our needs makes life more personal and real.

* If I own my needs, I actually lessen my demands on others because I'm living honestly.

Questioning ourselves in ways like this can help us overcome old cultural mind-sets that keep us from thinking about and figuring out what our needs are, what they're telling us about our lives, and how we need to pay attention to them. If we aren't aware of them they'll be down in our shadows, stirring up our unconscious energy and coming out in ways we don't intend them to. We have all known someone who puts on the facade of being self-sacrificing while actually being controlling and demanding attention. Or, we've found ourselves volunteering or being pressured to serve on some committee or in a campaign and then ending up feeling full of resentments.

Ignoring Our Needs Doesn't Make Us Happy

A few years ago a woman told me that she tried to ignore her needs because she thought that made it easier to be happy. Walling ourselves off to our needs doesn't make it easier to be happy. Before I figured out that I was repeating my father's patterns of not showing needs, I found myself resentful every year at my birthday about how thoughtless I felt my children were. I'd numbed my needs but not the hurt of feeling alone and unknown to the people closest to me. Our needs, especially our need for love and for people to love, have nothing to do with being selfish or self-indulgent. They have everything to do with being human.

Listening to our hearts, our minds, our bodies, our unconscious helps us realize our full humanity and its potentials. If we don't, we will be following the machine model of living and creating a wasteland in our souls and relationships. Most of us are brought up to believe that showing our emotions is embarrassing. Learning to hide them almost always means learning not to act on them. To become passionate whether it's from love, desire, suffering, or anger is a call to action and action can upset the sense of order on our islands. Acting on our emotions can sometimes bring shame or the appearance of being naive, out of control, or irrational. Many people in our culture, especially men, have become so used to hiding their emotions they're rarely sure of what they feel.

Robert was one of these men who didn't know what he felt. He thought he felt fine, but his wife and family doctor thought something was troubling him. They also thought he might be more upset about his upcoming fiftieth birthday than he realized. When I met Robert he was affable but there was also a sense of passivity around him that I felt right away. As I asked him a few questions I learned that he suffered from asthma and that it had recently gotten worse. I also concluded that down deep he had a suspicion his wife and doctor might be right in their belief that something was troubling him. But he couldn't figure out what it was.

During this first meeting we talked about his health and about his wife's concern, and he joked, as well, about turning fifty and gaining a little weight. Over the next few sessions we continued to talk casually and during each meeting he would quietly tell me a little more about his life, how good it was and why he couldn't understand why people were worried about him. Nonetheless at the end of each session he would schedule another meeting, as though some instinct was guiding him to do so. I felt that what was trying to emerge in Robert wasn't quite ready to be seen.

After a few sessions I noticed that as soon as Robert left my office I experienced a feeling of sadness, like a weight pushing my spirit down. After reflecting on these feelings for a while I decided to mention them to Robert. I said, "Robert we've gotten to know each other fairly well during the past few weeks and I've developed a lot of respect for you. But I want to tell you that after you leave my office I'm always left with a strong sense of sadness, of heaviness. What do you think about this?" At first Robert looked a little startled. Then, to both our surprise his eyes filled with tears.

Something inside of Robert was waiting until he was sure of the safety of my respect and confident in my ability to accept and understand him. Once feelings come out they're like a gift. To our everyday minds they may appear repugnant and frightening. In fairy tale terms our sadness often seems like a spell cast by an evil witch, and when it's broken beauty and peace return.

Our anger may seem like an ugly toad that when transformed can give us a renewed passion for life. And our fear may be an enchanted castle surrounded by a thicket of thorns that holds our abilities captive until they are freed by courage and determination. But folklore reminds us consistently that the things we normally despise are often princes or princesses in disguise.

Our Emotions Have A Purpose

Our emotions and the ways we experience them are never irrational or without purpose. Their logic is not of the mind but of the heart and its values. They're meant to lead us into new directions or understandings of life.

Many of us charge into adulthood with so much other-directed determination -- graduate school, internships, job interviews -- that we seldom consider our feeling states. Robert had done this and so had I. Today he's a successful stockbroker, but in his mid-twenties he was struggling, trying one job after another and feeling very worried about supporting his young family. When he began selling stocks he worked on commission and has now become a very respected money manager.

It turned out that he really is happy today and feels successful but cannot enjoy these feelings because of the burden of depression he is carrying from the past. He needed to go back in time and mourn for the young man with a family who had felt so lost and scared at times, practically in despair and who had worked relentlessly in spite of these feelings. He also needed to grieve for the time lost to work during the early years of his family when he'd wanted to participate with and enjoy his children. Yes, his fiftieth birthday was bringing these feelings to mind, and he invited his wife to join us for a few sessions in order to help him bring this new feeling dimension of himself into their relationship.

Looking Back to Honor Our Suffering

Life has its difficult side no matter how well we do. It's often very helpful and comforting to look back and honor our suffering and let it teach us to be more compassionate to ourselves and understanding of other people. Part of this hardship comes from the fact that to grow up or to become somebody we have to make choices. Whether we choose to be married or not, have children or not, work for success or find other rewards in life, or choose one career over another there is a price as well as a reward. Facing this reality and accepting the feelings that originally drove our choices or surrounded them, frees us to live without regrets.

Childhood wounds also surprise us by recycling themselves every time we move into a new stage of growth. I was devastated when my mother died in my early teens. Within a few years I thought I'd dealt with the experience. But its vibrations come up every time I go into a new phase of change that affects the way I perceive myself or life. In some ways, this early experience left a wound that was slower to heal than I could imagine, living deep within and making it difficult for me to trust life and relationships. But its effects over time has also toughened me, and given me a more refined sensitivity toward suffering.

Everyone has something from childhood that recycles. Fifty years later, a friend of mine vividly remembers a third grade teacher who shamed him in front of his classmates. A woman I know still recalls the acute loneliness and feelings of inferiority she felt when she was sent to an exclusive boarding school at an early age. She's told me how quickly that old feeling can return if she isn't careful when entering new situations.

Being Afraid of Our Feelings

Robert, like many of us, constructed a protective wall around his feelings because he was afraid of them. Over this wall he'd put on an illusion of feelings, a "person" of appropriate emotions who he'd come to believe was real. He thought he should feel happy so he put on a cheery act. He bought into the assumption that if we achieve the model of success in our society we should feel happy. But as he became more honest about how he felt he openly expressed his grief about life's difficult times and only acted happy when the feeling was genuine.

Several things indicate when we have walled off our feelings:

* Their absence. A lack of feelings, usually a coolness or remoteness, based on the mistaken belief that it's generally better to be nonemotional and objective.

* Being overly sentimental. An excess of ungrounded or undifferentiated feelings that come unexpectedly or in outbursts.

* Having mood states. Unexplainably going from high to low, or dropping into touchiness, sulkiness, criticism, self-criticism, or vulnerability.

Many of us are more disconnected from ourselves and each other than we realize. Our society is so image-oriented that it's easy to believe we feel something we don't feel. We think we feel good, are having fun, or feel angry because the circumstances make it look like that's how we should feel. And like Robert, we may paper over our feelings in order not to disturb people, or to get their approval. In fact, Robert may have received so much approval for being jovial and good-natured that he learned to admire that quality in himself even though it wasn't genuine.

From Judgment to Acceptance

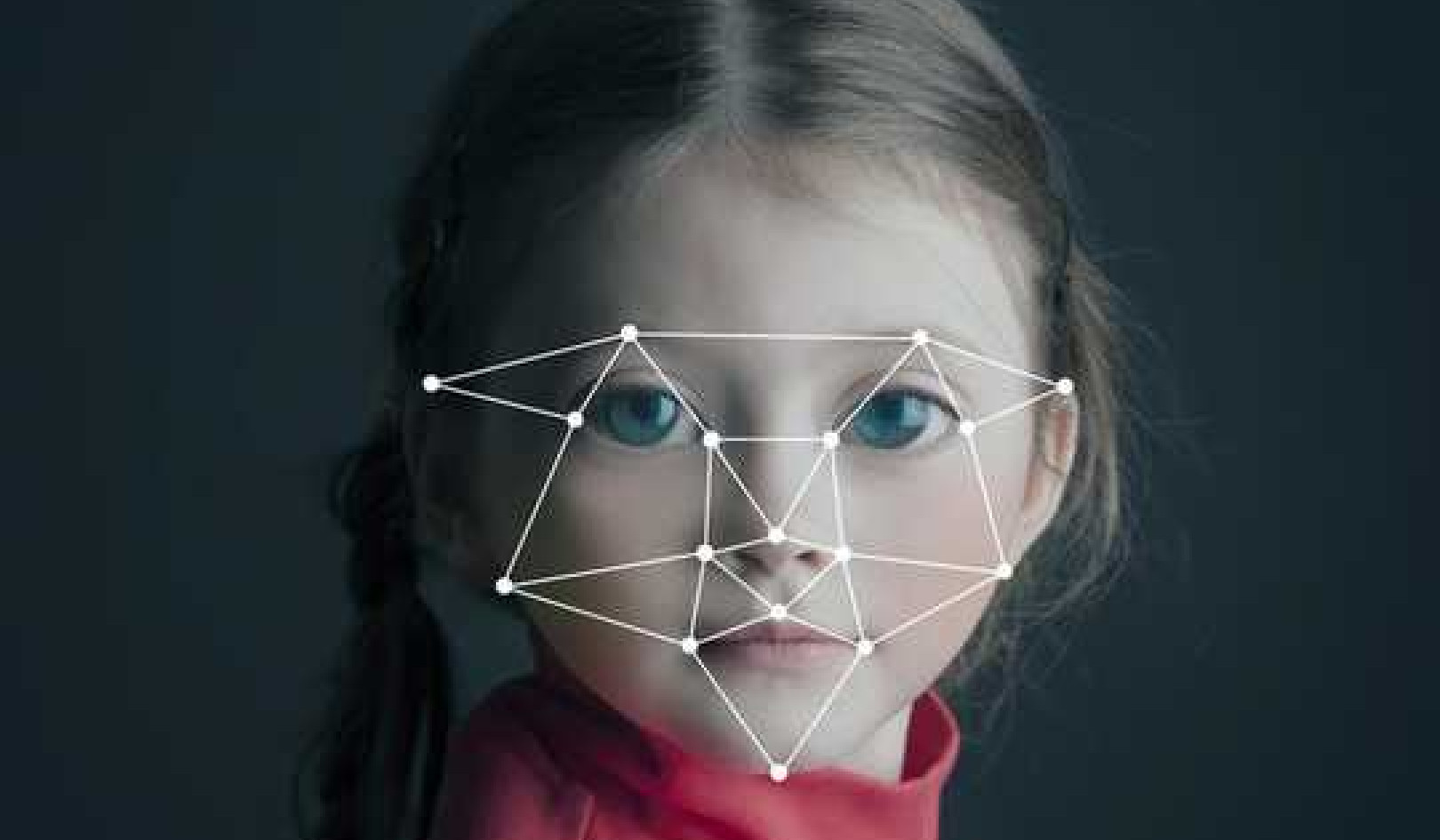

Understanding the ways in which we form our adult identities, and how we're influenced by the values of society and the traits it structures into our personalities, makes it easier to see how self-alienation is built into our existence. It begins as soon as we leave the womb and are launched into a process of being weighed and measured. Measurement in some form now accompanies almost every aspect of modern life. Ostensibly, measurement is supposed to be for our "own good" to monitor our health, growth, and capacities. As we grow and enter school it tells us how well we're doing, where we fall on the "growth chart," whether we have "potential," and if we're "living up" to that potential from the perspective of society's values. Almost before we realize it the emphasis on measurement is connected to our appearance, our performance, our behavior, and has been internalized into a personal mind-set. As we grow into adulthood everything from our sex lives to our credit ratings are evaluated from this perspective.

We're taught to judge ourselves relentlessly. The author and physician Naomi Remen observes that our vitality is diminished more by judgment than by disease. She goes on to explain that approval is just as damaging as a form of judgment as criticism. While positive judgment initially hurts less than criticism, it triggers a constant striving for more. It makes us uncertain of who we are and of our true value. Approval and disapproval spawn a compulsion to critically evaluate ourselves all the time. For example Judith won't go out for an evening with her husband and friends without spending an hour and a half putting on makeup. Harry can't do enough favors for everyone he tries to become friends with. And Matthew remains quiet and shy, preferring to be seen as a loner rather than to risk being rejected.

Desire for Approval

In a society that thrives on consumerism, we have become increasingly vulnerable. Advertising takes advantage of our obsession with self-judgment and desire for approval while holding out the promise that if we buy the right clothes, use the right makeup, follow the right diet, have the right appliances, yard tools, vacations, and so on, we can become happy and admired. Even the self-help industry has joined the caravan of marketing with books, tapes, videos, and workshops offering "quick fixes" to what's wrong with our lives rather than challenging us to look deeper into ourselves.

The marketing people are clever and know how to exploit our hopes and fears. Our social engine runs on performance and consumption. But we can face and change ourselves by developing enough self-knowledge to reclaim our lives, take initiative, have a viewpoint, love ourselves, and live in the world without being victimized by it.

After we'd been working together for a few months, Janice was reflecting on how she used to feel standing in front of that magazine rack in the drugstore. It was a pivotal moment for her. She said, "All of those self-improvement articles and advertisements make you feel you aren't good enough. That you're incomplete, inferior, inadequate. And what's supposed to make you feel better? Buying the magazine and buying the products. Now that's self-empowerment for you. Now that I've opened my eyes it seems like our whole culture is geared toward making you hate yourself and believing that buying more is the only thing that can help. It's like 'fix it, charge it.' But all you're really doing is keeping the system going."

Longing to Live a Meaningful Life

Janice is right. We're all born with an inner longing to live a meaningful life, to love and be loved. Advertisers have become skilled at redirecting these longings toward consumer goods, trying to convince us that inner needs can be satisfied with external things. They manipulate our needs to keep us off balance, anxious, and fearful of social isolation and loneliness. It is the modern equivalent of tribal banishment.

The system that drives our society promises that life can be good. But if we rely on the values of that system without growing beyond it into our own conscious awareness, all it will deliver is self-alienation.

To know that we are human is to know that life includes loss, darkness, and confusion, as well as magic and beauty. To become a mature, wise person requires that we come to know ourselves deeply and learn to navigate life's waters skillfully. Our growth depends upon our awareness of the reality we're experiencing. In turn, as this awareness grows, it will open us to further growth.

Knowing ourselves more fully, learning how to cultivate our inner resources and love ourselves in a substantial manner heals self-alienation and gives a firm foundation for letting the tides of culture flow around us without threatening us. Additionally, as we work on ourselves we must work on our society so that for future generations the term culture will return to its more substantial meaning of supporting enlightenment -- the development of intellectual, moral, and artistic potentials -- in a manner that can offer guidance to our children and grandchildren.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher,

Inner Ocean Publishing, Inc. ©2002. www.innerocean.com

Article Source:

Sacred Selfishness: A Guide to Living a Life of Substance

by Bud Harris.

In the tradition of Scott Peck’s The Road Less Traveled and Thomas Moore’s The Care of the Soul, Bud Harris shows us to value and love ourselves, to think for ourselves, to have lives of our own, and to be able to love others without losing ourselves. This is the path of sacred selfishness.

In the tradition of Scott Peck’s The Road Less Traveled and Thomas Moore’s The Care of the Soul, Bud Harris shows us to value and love ourselves, to think for ourselves, to have lives of our own, and to be able to love others without losing ourselves. This is the path of sacred selfishness.

Info/Order this book. Also available as a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Dr. Bud Harris has a Ph.D. in counseling psychology, and a degree in analytical psychology, finishing his postdoctoral training at the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich, Switzerland. He has over thirty years experience as a practicing psychotherapist, psychologist, and Jungian analyst. Visit his website at www.budharris.com