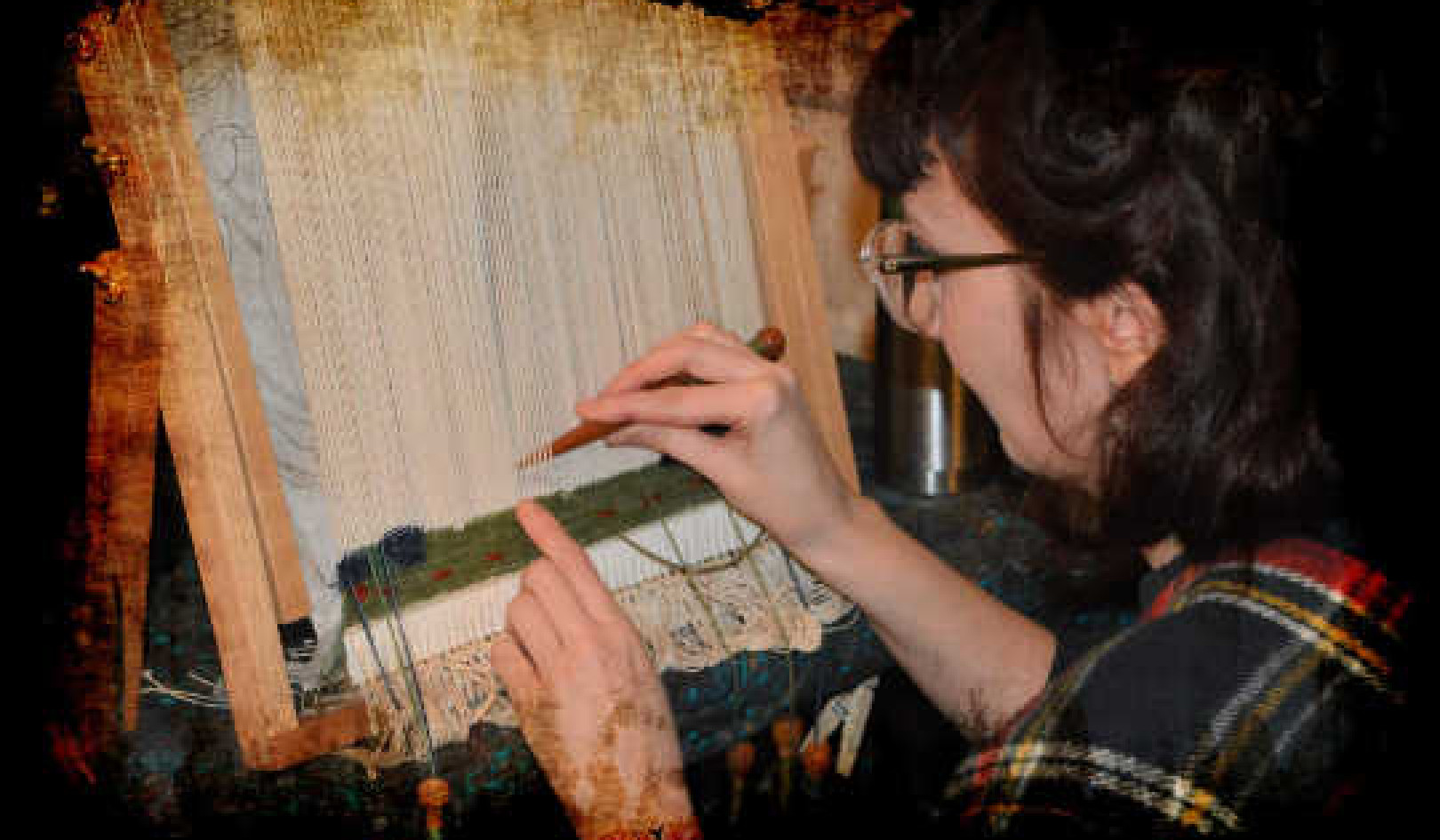

Australian government support for working mothers was minimal before the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. Shutterstock

Australian government support for working mothers was minimal before the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. Shutterstock

Over the past few decades of Australian life, government policies have gradually offered more support to working mothers, particularly through childcare subsidies and parental leave.

But what motivates Australian parents in their choices around work and childcare?

I’ve interviewed successive generations of Australian mothers to find out what combination of care and paid work they chose, and why. The results reveal a yawning gap in the way we talk about working families.

While our public debates remain solidly mired in the rational and the economic, mothers describe their decision-making processes as significantly motivated by emotions.

1970s: little support for working mothers

Australian government support for working mothers was minimal before the women’s liberation movement. Childcare services were introduced in the 1970s to support workforce participation of women, but working mothers were still considered controversial.

Sally’s story

Sally and her husband split the day into two halves after their first child was born in 1978, sharing paid work and caring responsibilities evenly:

…because I was the primary breadwinner, I went back when the child was just over six weeks old. […] I was half-time teaching and he was with the baby in the mornings. I’d come home, breasts engorged and ready to feed and then he’d go off and do his classes in the afternoons and evenings.

But Sally felt conflicted about whether she should be with her baby, and recalls that attitudes about working mothers and childcare were still fiercely contested.

1980s: navigating childcare shortages

Childcare services expanded under Labor governments in the 1980s, and legislation was passed with the intention of facilitating female employment. At the same time, Australian mothers faced continued obstacles to participating in the workforce, particularly a shortage of childcare that met their needs and desires.

Hazel’s story

Hazel’s progressive employer entitled her to maternity leave, and provided childcare on site. Although she felt judged by others for working when her child was young, she realised that the maintenance of her pre-maternal career was important for her emotional well-being:

I realised very early on, you know that your world contracts […] I wasn’t ever tempted to take more time off when I returned to work even though it was a juggle […] Somebody once said to me: happy mother, happy child, when I was worrying about going back to work. My mother-in-law, in particular, was very, very critical of that.

Genevieve’s story

Genevieve left her job in advertising when her first child was born because she felt that “mothering was a valuable role” and “a job that deserved respect and equal status”. But she felt some people judged women for “only” staying at home, and saw professional childcare as superior to maternal care:

That harping of, ‘Children love it! They’re so stimulated! They’d be bored at home! They’ve got all those toys, and they’re socialising with the other children, and it’s just fabulous’. I’d had this for years and years.

1990s: parental leave is introduced

Parental leave was introduced into federal awards in 1990, which entitled either parent to unpaid leave after the birth of a baby. In the 1990s, Australian views on whether mothers should engage in paid work, and whether children should be in childcare were mixed.

Caitlyn’s story

Living in a small regional town, Caitlyn says she felt judged for returning to paid work when her first born was 15 months old in 1991:

Childcare back then seemed like a dirty word. There was no childcare centres here […] and the fact that you would leave your child all day in someone else’s care kind of almost made you a bad parent because you were shirking your responsibilities or something…

Katherine’s story

Even in big cities, choices were limited. When Katherine’s partner’s part-time salary could not cover their expenses, she reluctantly went back to paid employment when her baby was three months old. Facing long waiting lists for local centres, she instead found a woman nearby who offered family day care:

…for me this whole thing of them going to one woman who may not have been perfect in every way, but she was their person, you know, it wasn’t an institution.

By the end of the 1990s, childcare was still viewed as the private responsibility (and problem) of women. Australian mothers increasingly engaged in paid work outside the home, but they continued to struggle amid an inconsistent policy environment that sent mixed messages.

2000s: new childcare subsidies

In a new tax benefit arrangement introduced in 2000, the Howard government granted working parents the right to 50 hours of childcare subsidy per week for each child, while non-salaried parents could claim 24 hours.

A 2005 survey of parental views of childcare found that:

- 27% were concerned about cost

- 22% couldn’t get a place at their preferred centre

- 20% couldn’t get the hours they needed

- 18% couldn’t find a service in the right location.

Time use surveys revealed that mothers managed this impossible juggle by reducing their own leisure time, so that the burden of inadequate policy supports fell upon them rather than employers or children.

Kristen’s story

Kristen had her first child in 2009 and decided not to return to paid employment until her youngest was in kindergarten. In her middle-class suburb of professional women, this decision has left her feeling socially isolated:

I have a friend […] who did the expected thing and went back to work after twelve months […] she was very stressed out, going back to work, and I’ve spared myself that stress and that anxiety by making a decision I had a very clear conscience about, as a mother […] Philosophically, for me, motherhood was easy –and I think in that regard, I was quite different from a lot of my friends…

2010s onwards: more support, but mixed emotions

From 2007 to 2013, Labor governments reformed early childhood education and care with the intention of building workforce participation, and therefore productivity. Government-funded maternity leave was introduced for the primary carer in 2011, and in 2013, dad and partner leave was introduced. Despite these gains, many mothers felt mixed emotions.

Rowena’s story

Rowena decided to work part-time around her mothering after watching her own mother battle with working full-time and feeling constantly guilty and stretched:

…if I’m lucky enough to have kids, I want to focus on you know having them and nothing else really matters as much. Like, people think they’re indispensable at work but everybody’s replaceable.

Changing the way we talk about child care

These accounts reflect a wide diversity of experiences of Australian mothers, but there are consistent threads in their narratives. Most mothers want some continuity with their pre-maternal identity, to feel a sense of meaningful contribution to their society, and to enjoy their relationships with their children.

If government fails to comprehend the reasons why mothers choose to engage with different supports, family policy will be of limited effectiveness. Workforce participation and economic productivity are reasonable objectives of government policy, but they are not sufficient on their own.

Ignoring the equally important objectives of maternal and child well-being risks exacerbating already high rates of perinatal depression and anxiety. Increasing numbers of Australian women will ask the reasonable question: why choose motherhood, when your society fails to adequately support that choice?

About The Author

Carla Pascoe Leahy, Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon