Image by Gerd Altmann

You never really understand a person

until you consider things from his point of view.

— Atticus Finch (in To Kill a Mockingbird)

Seeking to truly understand is a bold undertaking. You can’t understand another human being if you don’t listen.

Have you ever listened? I mean truly listened? Quieted your mind and surrendered all self-concern and given yourself completely to another person so that he or she is fully heard? If you’re really honest, the answer is likely no.

Deep Listening Isn’t Natural

Experience suggests that true, deep listening isn’t natural. And yet, most of us don’t really practice getting better at it. I believe you can consciously choose to become a much better listener and that being able to listen effectively can be one of the most rewarding skills you can develop.

Let’s start with why true, deep listening is worth focusing on. There are two primary benefits. The first has to do with the gift you are giving to the speaker when you listen fully.

Ask yourself how often you are listened to in a way that leaves you feeling complete. My guess is that the experience is rare for you. When you are heard in such a way, the experience is magical.

The second benefit is more utilitarian in nature. The more effective and complete your listening, the more data you have. The more data you have, the more accurate your decisions. The more accurate your decisions, the more effective you are. Put simply, more effective listening results in deeper relationships and more effective action. Count me in for working on being a better listener.

Listening Is Hard Work

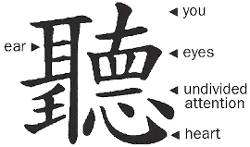

Yet, listening is hard work. It requires a full surrender of your entire being. The Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu captured just how difficult this is:

The hearing that is only in the ears is one thing. The hearing of the understanding is another. But the hearing of the spirit is not limited to any one faculty, to the ear, or to the mind. Hence it demands the emptiness of all the faculties. And when the faculties are empty, then the whole being listens. There is then a direct grasp of what is right there before you that can never be heard with the ear or understood with the mind. [Source: Thomas Merton, The Way of Chuang Tzu]

The Chinese symbol for “listen” contains a number of elements, including the ear, eye, and heart.

The Chinese symbol for “listen” contains a number of elements, including the ear, eye, and heart.

The technique of focusing on the speaker’s feelings and needs is perhaps the most effective way to give of yourself fully to the other person. Rather than seeing a speaker’s language as having anything to do with you, the key is to put aside your needs for the moment and look for the universal human feeling being experienced and the unmet need of the person speaking.

As Marshall Rosenberg explains, “We begin to feel this bliss when messages previously experienced as critical or blaming begin to be seen for the gifts they are: opportunities to give to people who are in pain.” [Source: Marshall Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication]

Practicing the Art of Listening

If full and complete listening is so powerful and yet so difficult to master, how do you begin to practice this art? Any new skillful behavior almost always begins with awareness of your program. So it is with listening.

In my work with business leaders, I offer the following powerful distinction to create an opening for awareness and for more effective listening: Every time you have a conversation, you bring to your listening the beliefs, values, and rules of your program. These rules constrain and distort what you hear so that what actually registers for you is different from the totality of what is said. I call this “default listening.”

In every situation with every person, you have a default listening for that situation and person. It is embedded in your program. And unless you are aware of that default listening, the rules you bring to a situation will shape and drive your listening in that situation.

Questioning Your Default Listening Mode

Consider the following example: Your default listening for a speaker at a conference might be “I already know.” It will follow that you will be listening only for data that confirm your “I already know” listening, and you will avoid or distort the information that you don’t know and should know.

This phenomenon is part of a larger truism—namely, that you tend to notice and select the data that confirm your existing beliefs. So if you are aware that you have an “I already know” default listening for a particular speaker or subject, you can then choose to try on a different default listening.

You might choose the following: “There is always something new I can learn from anyone about any subject.” This intentional choice of shifting from a subconscious, unexamined belief to a new, more far-reaching belief has the potential to expand your listening in a way that is meaningfully more effective.

Do you want to hold a belief that will lead to limited listening and engagement? Or do you want to consciously choose a mindset that allows for the possibility of growth and learning? Again, it is not whether the belief you choose is true or not, it’s whether it serves you. Questioning your default listening is about becoming aware of the beliefs you bring to your listening and then choosing a belief that best serves you in that situation.

Exercise:

Try this exercise right now. Identify a situation where you think you could benefit from more effective listening. Perhaps it is with your spouse, your child, or a work colleague.

What is your default listening for that person? Be honest.

It might be something like “I wish he would just get to the point.” Think about how that default listening might be impacting you. In this example, you may get easily distracted and frustrated with the person, causing the quality of your listening and your relationship to suffer.

Now, choose and experiment with a new default listening. It might be “I appreciate this person and want to give him the gift of my full attention.” Then notice what happens when you bring that listening into your conversation.

You might be surprised. Truly listening to this person might allow him to get to the point faster after all.

Thought, Consciousness, and Collective Intelligence

It is in group dialogue where the consequences of the lack of true listening are perhaps most acutely felt. If you’ve ever been frustrated in a team meeting or other group discussion, you will likely have experienced this phenomenon.

No one has done more to explore the dynamics of group dialogue than the physicist David Bohm. So influential was Bohm in the world of theoretical physics that Einstein considered him to be his “intellectual successor.” But it was in the domain of thought and consciousness, and specifically how groups tap into a deeper collective intelligence, that Bohm made some of his most important contributions. [Source: David Bohm, On Dialogue]

Expanding upon the principle in quantum physics that the universe is an indivisible whole, Bohm saw thought and intelligence as collective phenomena. Thus, he argued, in order to tap into our most creative thinking, we must do so through a certain type of collective discourse.

Discussion or Dialogue?

Bohm pointed to two principal forms of collective discourse—discussion and dialogue. The word “discussion,” Bohm noted, shares its roots with “percussion” and “concussion,” where the basic idea is to break things up. In a discussion, Bohm argues, the main point is to win—for your idea to prevail over the ideas of others.

Dialogue, as Bohm sees it, has a much different purpose. It is derived from the two Latin words dia, which means “through,” and logos, which means “the word.” “Dialogue” suggests a stream of meaning flowing through and between participants.

It is only when the conditions for this type of Bohmian dialogue are present that we can fully connect with the collective intelligence of the group. True dialogue allows participants to access a deeper intelligence, one that is universal and transcends the knowledge of the individual participants.

The Art and Science of Dialogue

Joseph Jaworski, author of the magnificent book Synchronicity and a student of Bohm’s, has spent much of his life teaching the art and science of dialogue. I have had the pleasure of getting to know Joseph personally. He is a treasure.

My favorite story of his is of a formative event during his time as a student at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. One afternoon in 1953, an historic tornado ripped through the college town, rendering much of it a wasteland. For the next twenty-four hours, Jaworski and a handful of strangers worked in harmony with one another, knowing exactly what was needed without having to say much of anything.

This experience, which Jaworski calls “unity consciousness,” was a defining moment in his life and set him on a search to discover the conditions that allow groups to access a deeper intelligence. That search led him to David Bohm and the practice of dialogue.

So how does one create the conditions for dialogue to emerge? The most important requirement is that we listen. And to listen, participants must be aware of their programs. For dialogue to occur, participants must be able to surface subconscious and unexamined assumptions. Once that happens, they have to be able to suspend those assumptions.

Bohm suggests that participants “neither carry [their assumptions] out nor suppress them.” Rather, he explains, “You don’t believe them, nor do you disbelieve them; you don’t judge them as good or bad. You simply see what they mean—not only your own, but the other people’s as well. We are not trying to change anybody’s opinion.”

In essence, Bohm was emphasizing the importance of awareness of our default listening and willingness to suspend our beliefs and assumptions.

The thing that mostly gets in the way of a dialogue is holding to assumptions or opinions, and defending them. If you are identified personally with an opinion, that would get in the way. And if you are identified collectively with an opinion, that also gets in the way. The main difficulty is that we cannot listen properly to somebody else’s opinion because we are resisting it—we don’t really hear it.

During a dialogue, a group is able to access greater collective meaning because, having transcended the need to defend their programs, participants are engaged in true listening.

Listening is Connection

So far, our discussion of listening has been admittedly somewhat mechanistic, implying the exchange of data and offering strategies for removing obstacles to the efficient and effective collection of such data. This understanding misses a critical aspect of listening— namely, that listening is an inherently intersubjective, relational act. No one does a better job of describing this than the American author Ursula K. Le Guin.

In her essay “Telling Is Listening,” Le Guin describes with exquisite beauty the intersubjective nature of communication, both in speaking and listening:

Any two things that oscillate at about the same interval, if they’re physically near each other, will gradually tend to lock in and pulse at exactly the same interval. Things are lazy. It takes less energy to pulse cooperatively than to pulse in opposition. Physicists call this beautiful, economical laziness mutual phase locking, or entrainment . . . When you speak a word to a listener, the speaking is an act. And it is a mutual act: the listener’s listening enables the speaker’s speaking. It is a shared event, intersubjective: the listener and speaker entrain with each other. Both the amoebas are equally responsible, equally physically, immediately involved in sharing bits of themselves. [Source: Ursula K. Le Guin, Telling Is Listening]

True listening isn’t thus merely a cognitive act, where you become aware of your assumptions and suspend those assumptions to be able to listen more effectively. Rather, it is an energetic state, one that requires your deep presence and attunement to the other person.

As Le Guin explains, “Listening is not a reaction, it is a connection. Listening to a conversation or a story, we don’t so much respond as join in—become part of the action.”

Now may be a good time to put down your reading for a minute and seek out a loved one. You can change the world if you change the way you listen.

©2019 by Darren J. Gold. All Rights Reserved.

Excerpted with permission from Master Your Code.

Publisher: Tonic Books. www.tonicbooks.online.

Article Source

Master Your Code: The Art, Wisdom, and Science of Leading an Extraordinary Life

by Darren J Gold

How does anyone get to a point in life where they can say unequivocally say that they feel fulfilled and fully alive? Why are some of us are happy and others unhappy despite almost identical circumstances? It’s your program. A subconscious set of rules that drive the actions you take and limit the results you get. To be extraordinary in any area of your life, you must write and master your own code. This is your guidebook for doing that now. (Also available as a Kindle edition, an Audiobook, and a hardcover.)

How does anyone get to a point in life where they can say unequivocally say that they feel fulfilled and fully alive? Why are some of us are happy and others unhappy despite almost identical circumstances? It’s your program. A subconscious set of rules that drive the actions you take and limit the results you get. To be extraordinary in any area of your life, you must write and master your own code. This is your guidebook for doing that now. (Also available as a Kindle edition, an Audiobook, and a hardcover.)

For more info, or to order this book, click here.

About the Author

Darren Gold is a Managing Partner at The Trium Group where he is one of the world's leading executive coaches and advisors to CEOs and leadership teams of many of the most well-known organizations. Darren trained as a lawyer, worked at McKinsey & Co., was a partner at two San Francisco investment firms, and served as the CEO of two companies. Visit his website at DarrenJGold.com

Darren Gold is a Managing Partner at The Trium Group where he is one of the world's leading executive coaches and advisors to CEOs and leadership teams of many of the most well-known organizations. Darren trained as a lawyer, worked at McKinsey & Co., was a partner at two San Francisco investment firms, and served as the CEO of two companies. Visit his website at DarrenJGold.com