Seeing the light at the end of the pandemic tunnel matters but teacher stress related to chronically under-serviced schools goes beyond COVID-19. (Shutterstock)

The teachers are not alright. As families across Canada juggle a variety of states of lockdown due to COVID-19, many teachers continue to voice concerns that government plans to keep students and teachers safe in schools are inadequate.

One fallout from the lack of support is that teachers are at risk of burnout, but the conditions for this precede the pandemic and speak to a much wider crisis of how governments fund and manage education.

Recent, and ongoing, research from Alberta sheds light on how teachers are coping and suggests broader questions exist about sustainable schooling conditions for students and teachers.

Increase in reports of mental health distress

In the fall of 2019, leaders from the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA) and Alberta School Employee Benefit Plan (ASEBP) noticed an alarming increase in reports of mental health distress from their membership of teachers, educational assistants and administrators. They partnered to sponsor a research study. In January 2020, I was asked to investigate the scope and experiences of compassion fatigue and burnout in Alberta educational workers.

Psychologist Charles Figley described compassion fatigue in 1995. He observed that therapists experienced symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder after working with traumatized clients. His work led to a new understanding of the heavy emotional, mental and physical cost to professionals who cared for vulnerable, hurting or grieving people.

Optimally, these professionals felt compassion satisfaction, the joy of helping other people through difficult life experiences. However, exposure to the pain and suffering of traumatized people could erode caregivers’ ability to effectively engage in caring work, potentially leading to compassion stress or, if left untreated, compassion fatigue.

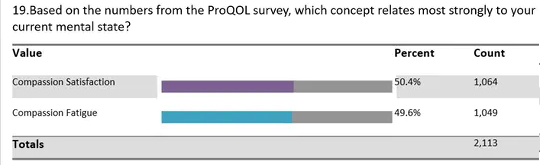

Recently, the first phase of this Alberta research study was completed. Phase one focused on the results of an online survey administered over a three-week period in June 2020, consisting of 28 closed and open-ended questions. Over 2,100 participants completed this survey, and the resulting statistics were grim.

Percentage of respondents who reported experiencing compassion fatigue. (Astrid Kendrick/ATA)

Collision of burnout and compassion fatigue

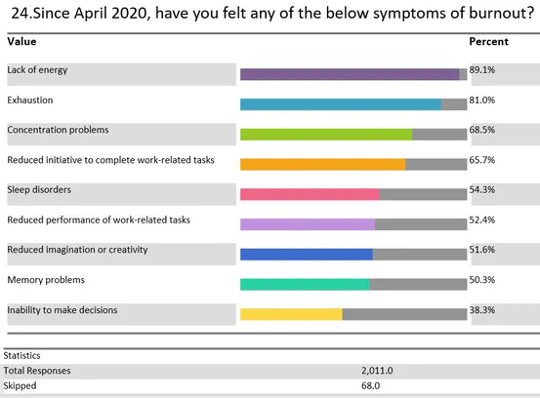

In addition to this alarming number of respondents reporting compassion fatigue, symptoms of burnout were also evident, including physical exhaustion and sensing a lack of feeling appreciated. Eighty-nine per cent of respondents reported feeling low energy and almost 70 per cent reported an inability to concentrate.

Fortunately, depersonalization, an extreme symptom of burnout characterized by a callousness or lack of caring towards students, was not evident. Conversely, respondents reported pushing themselves to exhaustion to meet the individual needs of their students.

Symptoms of burnout experienced by survey respondents. (Astrid Kendrick/ATA)

Alberta’s dismissal of many educational assistants and support staff early in the pandemic devastated the respondents who either lost crucial supports, or lost their own job, and could not help vulnerable students.

Ripe conditions for compassion fatigue

Compassion stress and compassion fatigue are widely accepted occupational hazards in caring professions such as nursing, firefighting, social work, emergency medical response or policing. An awareness of the signs and symptoms of these mental health problems are often part of professional training.

Teaching assistant Samuel Lavi works with an online class at the Valencia Newcomer School, Sept. 2, 2020, in Phoenix. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

However, only more recently has compassion fatigue been recognized as a problem for educators. The slow erosion of resources in and for schools, and the chronic underfunding of services for vulnerable and special needs students over the past several years, has resulted in an intensification of educators’ workloads. Rather than having other professionals and support staff to assist with the day-to-day running of schools, teachers and school administrators have taken over the jobs that hold school communities together.

As one survey participant noted:

“It’s not always about the big events or students with big trauma. It’s the day-to-day emptying of my bucket with no one there to fill it, decreasing understanding among administrators about this as well as decreasing respect for teachers from the general public. When I actually get to teach and help, I love it. The guilt of not being able to do it all is exhausting.”

The pandemic may be a traumatic event for students, therefore increasing the likelihood that educators will provide crisis and trauma support. Reports of increased domestic violence are particularly concerning. Educational caregivers, including teachers, administrators, support staff and facility workers need to recover from their burnout or compassion fatigue to provide the guidance needed for student success.

The consequences of ignoring educational caregivers’ burnout and compassion fatigue might lead to a high turnover of professionals, an inability to attract new employees and difficulty retaining experienced professionals .

People wait in a physical distancing circle at the yard at Portage Trail Community School in Toronto on Sept. 15, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nathan Denette

Attending to the risks of heartbreak

My earlier research focused on the ways that educators’ emotional labour can lead to occupational heartbreak. The next phase of this research project will focus on preventing compassion fatigue and burnout through purposeful training and planning and with the goal of protecting and healing educational workers’ hearts.

Healing can begin in four ways: understanding the impact of school culture, building wider community support for educators’ work, using personal self-care strategies and accessing professional supports and resources.

1. School culture

Numerous survey respondents described the impact of school culture on their mental and emotional well-being. Empathetic colleagues, time during the work day for self-care, a supportive parental community and positive mentorship from leaders characterized positive school cultures.

Conversely, toxic workplace culture was described as having adversarial collegial relations, inconsistent messaging around work/life boundaries, inadequate support from supervisors and a sense of helplessness regarding improving students’ learning conditions.

2. Community support

By reducing poverty and other social inequalities, and advocating for equitable public education, the local and provincial community can reduce the risk of children and youth experiencing crisis or trauma in the first place. In the short term, sincere gratitude from community members to educators, who pivoted the educational system to emergency remote instruction in a matter of months, is critical to build compassion satisfaction.

3. Individual self-care

Self-care is one aspect of individual recovery. The survey respondents suggested several ways they dealt with stress and distress, including exercising, using mindfulness practices, playing with their own children, walking their pets and connecting with nature.

4. Professional resources and supports

People experiencing either compassion fatigue or burnout should not be stigmatized. Instead, they should be encouraged to access professional support, such as seeing a doctor, therapist or psychiatrist, who are best trained to guide their recovery. Benefit providers and teacher associations can provide additional resources that have been tailored to the needs of educators.

Working with children and youth is a double-edged sword that can be rewarding and build compassion satisfaction, or challenging and lead to burnout and compassion fatigue. Understanding the unique nature of work in the educational field is an important aspect of ensuring that educators can emerge from the 2020 tunnel to flourish in 2021.

About the Author

Astrid H. Kendrick, Instructor, Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_education