Image by Gerd Altmann

We do not practice meditation to gain admiration from anyone. Rather, we practice to contribute to peace in the world. We try to follow the teachings of the Buddha, and take the instructions of trustworthy teachers, in hopes that we too can reach the Buddha's state of purity. Having realized this purity within ourselves, we can inspire others and share this Dhamma, this truth.

Buddha's teachings: Sila, Samddhi, and Panna

The Buddha's teachings can be summed up in three parts: sila, morality; samddhi, concentration; and panna, intuitive wisdom. Sila is spoken of first because it is the foundation for the other two. Its importance cannot be overstressed. Without sila, no further practices can be undertaken. For lay people the basic level of sila consists of five precepts or training rules: refraining from taking life, refraining from taking what is not given, refraining from sexual misconduct, refraining from lying, and refraining from taking intoxicating substances. These observances foster a basic purity that makes it easy to progress along the path of practice.

Sila is not a set of commandments handed down by the Buddha, and it need not be confined to Buddhist teachings. It actually derives from a basic sense of humanity. For example, suppose we have a spurt of anger and want to harm another being. If we put ourselves in that other being's shoes, and honestly contemplate the action we have been planning, we will quickly answer, "No, I wouldn't want that done to me. That would be cruel and unjust." If we feel this way about some action that we plan, we can be quite sure that the action is unwholesome.

In this way, morality can be looked upon as a manifestation of our sense of oneness with other beings. We know what it feels like to be harmed, and out of loving care and consideration we undertake to avoid harming others. We should remain committed to truthful speech and avoid words that abuse, deceive, or slander. As we practice refraining from angry actions and angry speech, then this gross and unwholesome mental state may gradually cease to arise, or at least it will become weaker and less frequent.

Of course, anger is not the only reason we harm other beings. Greed might make us try to grab something in an illegal or unethical way. Or our sexual desire can attach itself to another person's partner. Here again, if we consider how much we could hurt someone, we will try hard to refrain from succumbing to lustful desire.

Even in small amounts, intoxicating substances can make us less sensitive, more easily swayed by gross motivations of anger and greed. Some people defend the use of drugs or alcohol, saying that these substances are not so bad. On the contrary, they are very dangerous; they can lead even a good-hearted person into forgetfulness. Like accomplices to a crime, intoxicants open the door to a host of problems, from just talking nonsense, to inexplicable bursts of rage, to negligence that could be fatal to oneself or others. Indeed, any intoxicated person is unpredictable. Abstaining from intoxicants is therefore a way of protecting all the other precepts.

In a Meditation Retreat, Silence Is Appropriate

During a meditation retreat it becomes useful to change some of our conduct in ways that support the intensification of meditation practice. In a retreat, silence becomes the appropriate form of right speech, and celibacy that of sexual conduct. One eats lightly to prevent drowsiness and to weaken sensual appetite. The Buddha recommended fasting from noon until the following morning; or, if this is difficult, one could eat only a little in the afternoon. During the time one thus gains to practice, one may well discover that the taste of the Dhamma excels all worldly tastes!

Cleanliness is another support for developing insight and wisdom. You should bathe, keep nails and hair trimmed, and take care to regulate the bowels. This is known as internal cleanliness. Externally, your clothing and bedroom should be tidy and neat. Such observance is said to bring clarity and lightness of mind. Obviously, you do not make cleanliness an obsession. In the context of a retreat, adornments, cosmetics, fragrances, and time-consuming practices to beautify and perfect the body are not appropriate.

In fact, in this world there is no greater adornment than purity of conduct, no greater refuge, and no other basis for the flowering of insight and wisdom. Sila brings a beauty that is not plastered onto the outside, but instead comes from the heart and is reflected in the entire person. Suitable for everyone, regardless of age, station or circumstance, truly it is the adornment for all seasons. So please be sure to keep your virtue fresh and alive.

Even if we refine our speech and actions to a large extent, however, sila is not sufficient in itself to tame the mind. A method is needed to bring us to spiritual maturity, to help us realize the real nature of life and to bring the mind to a higher level of understanding. That method is meditation.

The Best Place For Meditation

The Buddha suggested that either a forest place under a tree or any other very quiet place is best for meditation. He said the mediator should sit quietly and peacefully with legs crossed. If sitting with crossed legs proves to be too difficult, other sitting postures may be used. For those with back trouble a chair is quite acceptable. It is true that to achieve peace of mind, we must make sure our body is at peace. So it is important to choose a position that will be comfortable for a long period of time.

Sit with your back erect, at a right angle to the ground, but not too stiff. The reason for sitting straight is not difficult to see. An arched or crooked back will soon bring pain. Furthermore, the physical effort to remain upright without additional support energizes the meditation practice.

Close your eyes. Now place your attention at the belly, at the abdomen. Breathe normally, not forcing your breathing, neither slowing it down nor hastening it, just a natural breath. You will become aware of certain sensations as you breathe in and the abdomen rises, as you breathe out and the abdomen falls. Now sharpen your aim and make sure that the mind is attentive to the entirety of each process. Be aware from the very beginning of all sensations involved in the rising. Maintain a steady attention through the middle and the end of the rising. Then be aware of the sensations of the falling movement of the abdomen from the beginning, through the middle, and to the very end of the falling.

Although we describe the rising and falling as having a beginning, a middle, and an end, this is only in order to show that your awareness should be continuous and thorough. We do not intend you to break these processes into three segments. You should try to be aware of each of these movements from beginning to end as one complete process, as a whole. Do not peer at the sensations with an overfocused mind, specifically looking to discover how the abdominal movement begins or ends.

In this meditation it is very important to have both effort and precise aim, so that the mind meets the sensation directly and powerfully. One helpful aid to precision and accuracy is to make a soft mental note of the object of awareness, naming the sensation by saying the word gently and silently in the mind, like "rising, rising ... falling, falling."

When Meditating, The Mind Will Wander

There will be moments when the mind wanders off. You will start to think of something. At this time, watch the mind! Be aware that you are thinking. To clarify this to yourself, note the thought silently with the verbal label "thinking, thinking," and come back to the rising and falling.

The same practice should be used for objects of awareness that arise at any of what are called the six sense doors: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind. Despite making an effort to do so, no one can remain perfectly focused on the rising and falling of the abdomen forever. Other objects inevitably arise and become predominant. Thus, the sphere of meditation encompasses all of our experiences: sights, sounds, smells, tastes, sensations in the body, and mental objects such as visions in the imagination or emotions. When any of these objects arise you should focus direct awareness on them, and use a gentle verbal label "spoken" in the mind.

During a sitting meditation, if another object impinges strongly on the awareness so as to draw it away from the rising and falling of the abdomen, this object must be clearly noted. For example, if a loud sound arises during your meditation, consciously direct your attention toward that sound as soon as it arises. Be aware of the sound as a direct experience, and also identify it succinctly with the soft, internal verbal label "hearing, hearing." When the sound fades and is no longer predominant, come back to the rising and falling. This is the basic principle to follow in sitting meditation.

In making the verbal label, there is no need for complex language. One simple word is best. For the eye, ear, and tongue doors we simply say, "Seeing, seeing... Hearing, hearing... Tasting, tasting." For sensations in the body we may choose a slightly more descriptive term like warmth, pressure, hardness, or motion. Mental objects appear to present a bewildering diversity, but actually they fall into just a few clear categories such as thinking, imagining, remembering, planning, and visualizing. But remember that in using the labeling technique, your goal is not to gain verbal skills. Labeling technique helps us to perceive clearly the actual qualities of our experience, without getting immersed in the content. It develops mental power and focus. In meditation we seek a deep, clear, precise awareness of the mind and body. This direct awareness shows us the truth about our lives, the actual nature of mental and physical processes.

Meditation Need Not Come To An End

Meditation need not come to an end after an hour of sitting. It can be carried out continuously through the day. When you get up from sitting, you must note carefully -- beginning with the intention to open the eyes. "Intending, intending... Opening, opening." Experience the mental event of intending, and feel the sensations of opening the eyes. Continue to note carefully and precisely, with full observing power, through the whole transition of postures until the moment you have stood up, and when you begin to walk.

Throughout the day you should also be aware of, and mentally note, all other activities, such as stretching, bending your arm, taking a spoon, putting on clothes, brushing your teeth, closing the door, opening the door, closing your eyelids, eating, and so forth. All of these activities should be noted with careful awareness and a soft mental label.

Apart from the hours of sound sleep, you should try to maintain continuous mindfulness throughout your waking hours. Actually this is not a heavy task; it is just sitting and walking and simply observing whatever occurs.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Wisdom Publications.

©1992, 1995 by Saddhamma Foundation. www.wisdompubs.org

Article Source

In This Very Life: Liberation Teachings of the Buddha

by Sayadaw U. Pandita.

Burmese meditation master Sayadaw U Pandita shows us that freedom is as immediate as breathing, as fundamental as a footstep. In this book he describes the path of the Buddha and calls all of us to that heroic journey of liberation.

Burmese meditation master Sayadaw U Pandita shows us that freedom is as immediate as breathing, as fundamental as a footstep. In this book he describes the path of the Buddha and calls all of us to that heroic journey of liberation.

Enlivened by numerous case histories and anecdotes, In This Very Life is a matchless guide to the inner territory of meditation - as described by the Buddha.

Info/Order this book. Also available as a Kindle edition.

About the Author

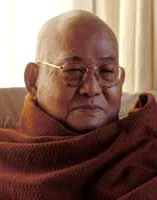

Sayadaw U Pandita-Bhivamsa entered the Mahabodhi Monastery at the age of seven. Sayadaw U Pandita was considered to be one of the leading authorities in the practice of Satipatthana as taught by his instructor the late Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw. He possessed extensive knowledge in both the theory and practice of Samatha and Vipassana meditation.

Sayadaw U Pandita-Bhivamsa entered the Mahabodhi Monastery at the age of seven. Sayadaw U Pandita was considered to be one of the leading authorities in the practice of Satipatthana as taught by his instructor the late Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw. He possessed extensive knowledge in both the theory and practice of Samatha and Vipassana meditation.

For over 40 years Sayadaw served as spiritual advisor to retreat centers, monasteries and Buddhist organizations throughout the world. From 1951 to 2014, he traveled to many countries to lead meditation retreats. Formerly the head "abbot" of Mahasi Sasana Yeiktha, in 1993 he became the Ovadacariya Sayadaw (head preceptor, highest position for monks) of Panditarama Monastery in Yangon, Myanmar.

For more info., visit http://www.saddhamma.org/Teachers.html.