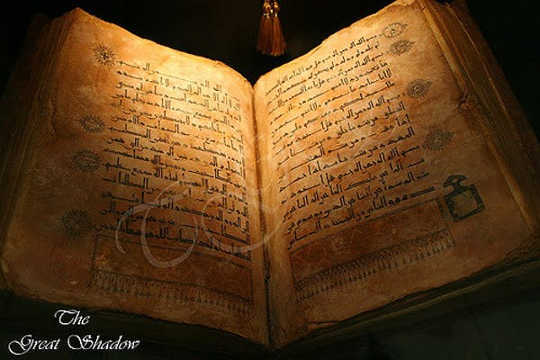

Jefferson purchased a Qur'an much before drafting the Declaration of Independence. SSk Graphy, CC BY

An estimated 3.3 million American Muslims celebrate Ramadan.

The month of Ramadan marks the time when Prophet Muhammad is believed to have first received revelations from God and has been celebrated at the White House since 1996. It was Hillary Clinton who started the tradition as first lady. However, last year, the Trump White House did not host the traditional reception. Neither did the State Department under Secretary Rex Tillerson, even though the holiday has been commemorated there since 1999.

After last year’s deliberate break with tradition, President Donald Trump has resumed the iftar dinner – the sundown meal during the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan. Despite the relatively recent nature of these formal celebrations, the fact is that Islam’s presence in North America dates to the founding of the nation, and even earlier, as my book, “Thomas Jefferson’s Qur'an: Islam and the Founders,” demonstrates.

Islam, an American religion

Muslims arrived in North America as early as the 17th century, eventually composing 15 to 30 percent of the enslaved West African population of British America. Muslims from the Middle East did not begin to immigrate to the United States as free citizens until the late 19th century. Key American Founding Fathers demonstrated a marked interest in the faith and its practitioners, most notably Thomas Jefferson.

As a 22-year-old law student in Williamsburg, Virginia, Jefferson bought a Qur’an – 11 years before drafting the Declaration of Independence.

The purchase is symbolic of a longer historical connection between American and Islamic worlds, and a more inclusive view of the nation’s early, robust view of religious pluralism.

Although Jefferson did not leave any notes on his immediate reaction to the Qur’an, he did criticize Islam as “stifling free enquiry” in his early political debates in Virginia, a charge he also leveled against Catholicism. He thought both religions fused religion and the state at a time he wished to separate them in his commonwealth.

Despite his criticism of Islam, Jefferson supported the rights of its adherents. Evidence exists that Jefferson had been thinking privately about Muslim inclusion in his new country since 1776. A few months after penning the Declaration of Independence, he returned to Virginia to draft legislation about religion for his native state, writing in his private notes a paraphrase of the English philosopher John Locke’s 1689 “Letter on Toleration”:

“(He) says neither Pagan nor Mahometan (Muslim) nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion.”

The precedents Jefferson copied from Locke echo strongly in his Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which proclaims:

“(O)ur civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions.”

The statute, drafted in 1777, became law in 1786 and inspired the Constitution’s “no religious test” clause and the First Amendment.

Jefferson’s pluralistic vision

Was Jefferson thinking about Muslims when he drafted his famed Virginia legislation?

Indeed, we find evidence for this in the Founding Father’s 1821 autobiography, where he recorded that a final attempt to add the words “Jesus Christ” to the preamble of his legislation failed. And this failure led Jefferson to affirm that he had intended the application of the Statute to be “universal.”

By this he meant that religious liberty and political equality would not be exclusively Christian. Jefferson asserted in his autobiography that his original legislative intent had been “to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan [Muslim], the Hindoo, and Infidel of every denomination.”

By defining Muslims as future citizens in the 18th century, in conjunction with a resident Jewish minority, Jefferson expanded his “universal” legislative scope to include every one of every faith.

Ideas about the nation’s religiously plural character were tested also in Jefferson’s presidential foreign policy with the Islamic powers of North Africa. President Jefferson welcomed the first Muslim ambassador, who hailed from Tunis, to the White House in 1805. Because it was Ramadan, the president moved the state dinner from 3:30 p.m. to be “precisely at sunset,” a recognition of the Tunisian ambassador’s religious beliefs, if not quite America’s first official celebration of Ramadan.

A White House tradition

Muslims once again provide a litmus test for the civil rights of all U.S. believers. Even though this administration resumes the traditional White House Ramadan celebration in 2018, many prominent American Muslims have publicly stated that, even if invited, they would not attend. Many American Muslim have not forgotten Trump’s many wrong assertions against them. Currently, the legality of this administration’s Muslim ban is pending before the Supreme Court.

Regardless of the stated anti-Islamic political views of this president, Ramadan still provides a moment to remember that Islam has long been practiced in America. Its adherents remain a pivotal part of its founding history. The presence of Muslims in America, as American citizens, has now been acknowledged by the Trump administration, in this year’s markedly more inclusive 2018 statement about Ramadan. The statement reads in part:

“Ramadan reminds us of the richness Muslims add to the religious tapestry of American life. In the United States, we are all blessed to live under a Constitution that fosters religious liberty and respects religious practice.”

Today, Muslims are fellow citizens, and their legal rights represent an American founding ideal still besieged by fear mongering, a practice at odds with the best of our ideals of universal religious freedoms. Despite demonstrating more public hostility toward Islam than any previous administration, the White House celebration of Ramadan this year underscores a more important, implicit historical reality: Muslims have practiced their faith here for centuries and will continue to do so.

About The Author

Denise A. Spellberg, Professor of History and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Texas at Austin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon