Image by Merlin Lightpainting

Narrated by the author.

Watch video version at InnerSelf.com or on YouTube

Many skilled Western meditators have noted an uncomfortable gap between their “spiritual” aspect and their everyday personality. For some, it is tempting to use meditation to withdraw from unpleasant feelings or relationship conflicts into a meditative “safe zone.”

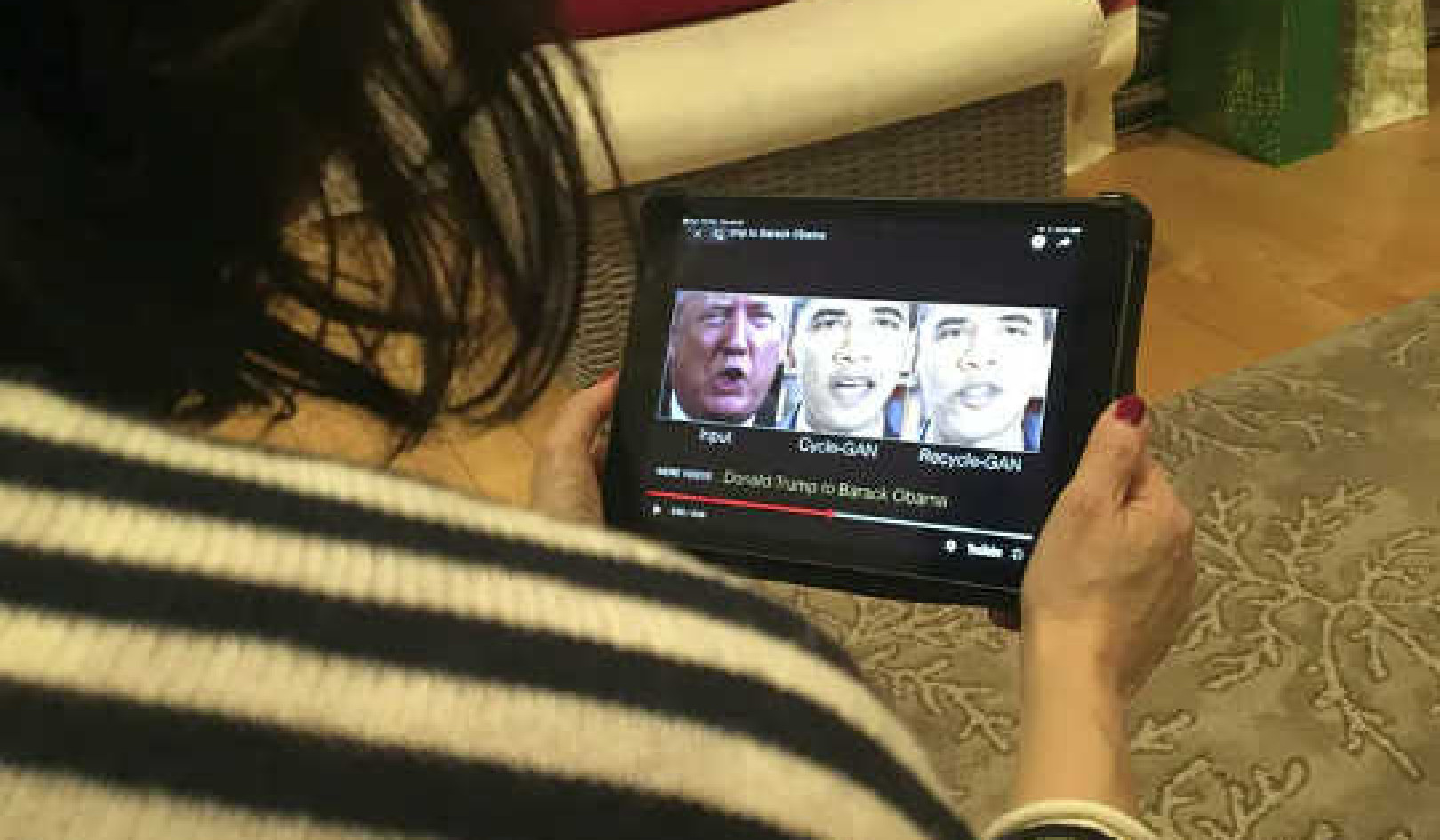

One representative example is found the online magazine Aeon. In July 2019, it brought a thoughtful article, “The Problem of Mindfulness,” from a university student, Sahanika Ratnayake.

Sahanika had begun to meditate in her teenage years and then found that the very practice of neutral witnessing interfered with her ability to form judgments about the situations that she was in. She felt as if a membrane had formed between her and the events of her life and the events in the news.

Very sensibly, she ended up using neutral witnessing much more sparingly—and I suspect that loving-kindness meditations might have been helpful as well. What she experienced was not meditative witnessing but dissociation.

Meditation and Immaturity

Other meditators long for glowing visions of divine figures or intricate dreams and past-life images of their spiritual belonging or importance—events that can counterbalance low self-esteem. Others seem to seek refuge in performance: counting daily hours of meditation, collecting data on time spent as a quality guarantee for a valuable life.

Also, a sense of entitlement can easily sneak in: “Because I am such a good and spiritual person, I am entitled to . . . (your love and admiration, your money, sex with you whether you want it or not, the right to throw temper tantrums, the right not to get criticized, not to get disturbed)”—fill in your own favorite privilege. Of course, this is not spirituality but immaturity.

Seeking Comfort

It is important to realize that meditation and prayer don’t automatically create a mature personality. They develop skills in meditating and praying. Interestingly, modern Jungian psychologists have been very alive to this issue.

One excellent author on the subject is Robert Moore, whose descriptions are much with me. He writes about the immature tendency to seek comfort in grandiosity (Moore, 2003). In his view, grandiosity can be either directly self-centered (“I am amazing”) or referred to the group that a person identifies with (“I have the true religion/football team/et cetera)” or to a teacher (“I myself am nothing, but my spiritual teacher or organization is the one true way,” or at the very least “My teacher and spiritual path are better than your teacher and spiritual path”).

Spiritual Sensitivity

Another pitfall is “spiritual sensitivity,” which can be understood as being too sensitive to bear facing the pain of other people or of the world. This position is not exclusive to people with a spiritual practice, and it is also not a sign of purity, but the result of being caught at the maturation level of emotional contagion.

This term refers to the normal emotional maturity that is most evident in the infant at around three to eight months of age. It describes states in which we resonate with the feeling of another person but get caught in that feeling instead of being able to embrace it, feeling it fully and holding it with kindness.

Empathy and Maturation

When we can access slightly higher levels of maturity, we feel more separate, and this makes it possible to develop empathy. This emerges around the age of sixteen to eighteen months of age, and it transforms our emotional resonance into a feeling of care directed to the other.

From empathy we can take a step further in maturation, developing the ability to create a mental image of what the other is experiencing and then reality-testing it—checking it, combining mental clarity with empathy into an attitude of compassion that reaches out to the actual need rather than to our fantasy of the need.

More Meditation Pitfalls

But we are not quite done with the pitfalls. Once we can think about the inner states of others, we can lose the empathic resonance in favor of a safe mental ivory tower of thoughts, explanations, and disengaged mirror-like witnessing. Compassion is the opposite of disengagement. Itliterally means “with-passion” or “in-touch.” We touch pain and joy and allow it to touch us and move us, and perhaps move us to action—but not to drown us.

I might add a final, universal, primitive dynamic: “us” versus “them.” Once again, these issues are not caused by contemplative practices (or religion in general), but contemplative practices do not resolve them. If they did, groups with a high value on prayer and meditation would have little or no conflict, their leadership would be free of aggressive or underhanded competition, and their organizational hierarchies would be helpful and benign. Splitting into “us” and “them” just wouldn’t happen. Perhaps we would have just one inclusive world religion in which everyone would be able to find common ground and accept each other’s inevitable differences.

Instead, the social dynamics of spiritual organizations and spiritual leadership look just like that of all the other human activities, from war to politics to football to cooking, with mature and immature behavior all mixed together, scandals, infighting, great teamwork here and there, greed, power games, lies, compassionate behavior, sexual abuse, and all the rest of the whole glorious mess of human social life.

The hard fact of human maturation and brain development is that you get better at what you do more of, and you lose skills that you don’t use. Learning meditation and prayer will not make us better at resolving conflicts with other people, because the two practices require different skill set. Meditating will make you better at meditating.

Learning to resolve conflicts in relationships

Faced with questions from students about deeply personal problems and existential issues, many meditation masters have come up with a compassionate cry: “Meditate more! Let go! It will pass!” This is true, everything will pass, including us, but in the meantime, maturity is about taking responsibility for something more than our own comfort or development.

In this century, we are waking up to sharing the care of a whole world. In your daily relationships, this means that no matter how innocent, pure, or spiritual you might feel, if there is a conflict in one of your relationships, understanding yourself as part of this conflict is an essential skill. Learning to work well with others and learning to resolve painful issues in your intimate life and your friendships will develop this skill. It will also give you more depth if and when you meditate.

Learning to resolve conflicts in relationships is likely to enhance your spiritual practice, if you have one. In exactly the same way, a spiritual practice is likely to help you with your relationship issues, if you want to learn how to resolve relationship pain. All learning has an innate structure. It adapts to other fields. Once you know three languages well, a fourth is easier to learn.

In my own experience, it holds true that deep insights about learning transfer well across different fields, such as meditation, relationship issues, and animal training. As I continue to learn how to train a dog or a horse, as well as my recently adopted red-tailed boa Cassie, I improve my ability to listen into animals. During that often frustrating process, I develop nonverbal cues and discover nonverbal principles of how to listen to the aliveness and readiness of my own consciousness—and how to listen to the aliveness of students, clients, friends, and last, but not least, my husband.

Copyright 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted with permission. Publisher.

Healing Arts Press, an imprint of Inner Traditions Intl.

Article Source:

Neuroaffective Meditation

Neuroaffective Meditation: A Practical Guide to Lifelong Brain Development, Emotional Growth, and Healing Trauma

by Marianne Bentzen

Drawing on her 25 years of research into brain development as well as decades of meditation practice, psychotherapist Marianne Bentzen shows how neuroaffective meditation--the holistic integration of meditation, neuroscience, and psychology--can be used for personal growth and conscious maturation. She also explores how the practice can help address embedded traumas and allow access to the best perspectives of growing older while keeping the best psychological attitudes of being young--a hallmark of wisdom.

Drawing on her 25 years of research into brain development as well as decades of meditation practice, psychotherapist Marianne Bentzen shows how neuroaffective meditation--the holistic integration of meditation, neuroscience, and psychology--can be used for personal growth and conscious maturation. She also explores how the practice can help address embedded traumas and allow access to the best perspectives of growing older while keeping the best psychological attitudes of being young--a hallmark of wisdom.

The author shares 16 guided meditations for neuroaffective brain development (along with links to online recordings), each designed to gently interact with the deep, unconscious layers of the brain and help you reconnect. Each meditation explores a different theme, from breathing in “being in your body”, to feeling love, compassion, and gratitude, to balancing positive and negative experiences. The author also shares a 5-part meditation centered on breathing exercises designed to balance your energy.

For more info and/or to order this book, click here. Also available as a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Marianne Bentzen is a psychotherapist and trainer in neuroaffective development psychology. The author and coauthor of many professional articles and books, including The Neuroaffective Picture Book, she has taught in 17 countries and presented at more than 35 international and national conferences.

Marianne Bentzen is a psychotherapist and trainer in neuroaffective development psychology. The author and coauthor of many professional articles and books, including The Neuroaffective Picture Book, she has taught in 17 countries and presented at more than 35 international and national conferences.

Visit her website at: MarianneBentzen.com