We who value tolerance sometimes behave as if we think tolerance is the ultimate value of the liberal spirit, a cure for all the ills of society. But, tolerance always has limits, and ultimately, tolerance ends in intolerance.

For example, we may tolerate wide differences in lifestyle and religious practice. We allow people to follow their own faith even if it is not congruent with ours, as long as they do not demand that we subscribe to their philosophy. If they insist that women may not participate in the public life of their church, then their church is the loser, but if the women do not object, we feel that we can ignore it. If they demand that men wear long beards, or that all members refrain from wearing bright colors, or that women veil themselves in public, again we may wonder how anybody can subscribe to such ideas, but we agree that they can do what they want.

Tolerance can allow for a wide range of beliefs and practices, provided that we come from basically similar cultures. But what if your next-door neighbors come from a part of the world where their homeland custom demands that the man beat his wife if she does not obey him quickly enough?

There is a limit to tolerance within our own culture in America. For most liberal-minded folks, gay and lesbian people are respected and welcomed; so are neighbors of different races. We welcome Jewish neighbors, Gentile neighbors, Muslim neighbors, Christian neighbors, as well as black, brown, or white neighbors. But what about neighbors who are skinheads or neo-Nazis, and what about those whose religion condemns all other spiritual practices and who strive for a society governed by their own narrow vision? Shall we ignore their efforts?

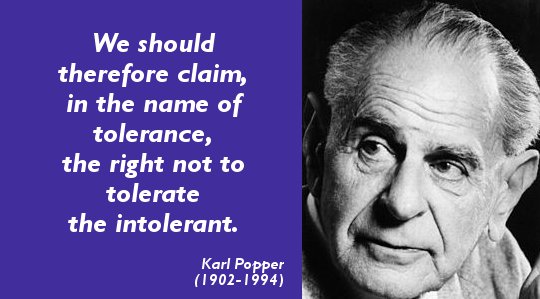

Tolerance Is Not Endless: It Does Not Tolerate Intolerance

Some zealous religious believers often do a great deal of good in charitable projects; they may be honest, trustworthy, and lovingly concerned. But do we allow them to capture control of the local school board so that they can censor the scientific curriculum?

The paradoxical ethical reality that we must face is this: tolerance is not endless, and ultimately, tolerance cannot tolerate intolerance. As we decide to live our faith, whatever the specific content of the commitment, we must make a variety of interconnected decisions, and each person and each family must follow its own personal integrity. Along the way, some things become clear:

* If any human society is to survive, it must have agreed-on rules.

* In general, it is better to follow the rules, but in some situations we must break them in order to honor a higher principle.

* The proscription against murder must be a high priority.

* We must respect others' rights to their possessions and be honest in our day-to-day lives.

* We must respect marriage and partnerships.

* The ability to trust your companions is a fundamental principle of survival.

* Integrity is essential: we grow spiritually when we act from inner authenticity in all situations.

Situation Ethics: What Does Love Say Should Be Done Here?

In 1966, Episcopal priest Dr. Joseph Fletcher published a book entitled Situation Ethics. The book was both roundly condemned and highly praised. Some thought it was not stringent enough in setting forth a specific moral code. Others, however, saw it as a watershed work in clarifying moral theology.

Fletcher distinguishes three approaches to making moral decisions, and although his system grows out of the Christian tradition, it can work as a guide for non-Christians as well.

(1) The legalistic stance approaches any decision-making situation with a whole set of interlocked rules and laws. These laws are not guides, but demands for obedience. Since life is complicated and situations change, there are multitudes of additional sub-rules. Fletcher observes, "Statutory and code law inevitably piles up ... because the complications of life (and the claims of mercy and compassion) combine ... to accumulate an elaborate system of exceptions and compromises, in the form of rules for breaking the rules! "

(2) Antinomianism (against all laws) approaches every situation afresh and without any general principles: you just make it up as you go along. It is totally unpredictable and it cannot be called an ethical system, for it has no way to think of what might be better or worse and no approach to right or wrong.

(3) Situationism acknowledges the rules and principles of the tradition in which it seeks to operate. These rules may illuminate every decision. Yet, the situationist is ready to modify or compromise if the situation demands it. He allows the function of reason and natural law; he acknowledges the high values of scripturally-based ethics. But the situationist abides by one central value, namely, love of neighbor. She acknowledges that circumstances alter cases; she knows that a specific situation may demand an unusual decision, and she asks, "What does love say should be done here?" The basic strategy is to apply love (or the highest good) to the situation, and reach a decision within that context.

Love as the Guiding Principle in Making Ethical Decisions

Love, the commitment to the highest good for all, is not to be bartered away. Keep in mind that love for other people is not a feeling; it is an attitude by which we approach choice, and it serves as the guiding principle in making ethical decisions.

Let us consider, as an example, the heroine of the apocryphal Book of Judith. It is set in the time of the Assyrian conquest of Israel, about 720 BCE. Judith is a wealthy and pious widow. She is diligent in prayer, obedient to the rules of mourning, observant of the dietary laws, and considered a saint by the people around her. When her town is surrounded by enemy troops under General Holofernes, Judith executes a daring plan: she dresses herself beautifully and makes her way to Holofernes' camp. She is taken to the general by guards, and she (1) lies to gain his confidence, (2) flatters and flirts with him, (3) gets him drunk so as to (4) seduce him into thinking he can sleep with her, and when he is in a stupor, she (5) cuts off his head. At the end she is regarded not only as a saint, but also as a savior-heroine.

Judith set aside her personal piety and natural obedience to rules in order to save the people of her village, and her story illustrates that when ethical principles are in conflict, one must choose the way that will benefit the most people. There is no such thing as a flawless set of rules that will always give an error-free answer to ethical problems, but this principle can give guidance even in complex situations.

Real life is complex and far from certain. Yet we have many responsibilities, and although the universe is not fair, we can seek fairness and justice in our relationships. We are star-stuff with power to make decisions; we are a part of the Universe that can make decisions and try to bring order out of its perplexities. It will not be done for us; we must do it ourselves. And that is how we live.

©2001. Reprinted with permission of the publisher,

Quest Books, Theosophical Publishing House,

www.questbooks.net

Article Source

Finding Faith in the Face of Doubt: A Guide for Contemporary Seekers

by Joseph S. Willis.

Many Americans say they are uncertain about their religious beliefs, although they continue to attend Christian and other churches. Interdenominational minister Willis presents this beautifully written book to help questioners maintain their integrity while relating to the vast Mystery that informs the universe beyond all understanding. "We know we don't know," Willis says, "and yet we all (even atheists) must stand on assumptions that help us lead good lives." To explore these assumptions, he discusses different ways of thinking about God, scientific and mythical views, the sources of good and evil, and the need for both freedom and commitment. He assures us we can all think reasonably about Ultimate Reality and find a faith that fits.

Many Americans say they are uncertain about their religious beliefs, although they continue to attend Christian and other churches. Interdenominational minister Willis presents this beautifully written book to help questioners maintain their integrity while relating to the vast Mystery that informs the universe beyond all understanding. "We know we don't know," Willis says, "and yet we all (even atheists) must stand on assumptions that help us lead good lives." To explore these assumptions, he discusses different ways of thinking about God, scientific and mythical views, the sources of good and evil, and the need for both freedom and commitment. He assures us we can all think reasonably about Ultimate Reality and find a faith that fits.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book.

About the Author

Joseph S. Willis is Minister Emeritus of Jefferson Unitarian Church in Golden, Colorado. A former Presbyterian minister, he was campus pastor at the University of New Mexico where he worked with Catholic and Jewish groups to create the Interreligious Council. He taught college theology courses and, now retired, still teaches at Unitarian and Methodist churches.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon