Society has become increasingly preoccupied with risk. So it’s unsurprising that as social scientists, we are constantly being asked to predict where harm is most likely to strike. In terms of crime and disorder – our speciality – we know a small number of places and people suffer the majority of victimisation. Using this knowledge, we know that anti-social behaviour peaks around Halloween and that violence is more common in the summer, especially on unusually warm days.

But when asked to identify the most dangerous day of the year, we realised this research hadn’t been done. Perhaps the reason for this is the wide variety of risk that creates unnatural or accidental death – from workplace incidents, to road accidents and crime. But this is an important question, as avoiding such risk can benefit our sense of well-being and also the economy.

Governments and academics have previously estimated the cost surrounding death and injury, using such criteria as health costs (including relatives who suffer loss), lost output (such as wages) and service charges (such as ambulance; police costs; damage to property; and insurance administration). These calculations show homicide is the most costly incident resulting in death, estimated at £3.2m per case, while the average cost per suicide is £1.7m.

And although overall road accidents have been decreasing, pedestrians, bicyclists and motorcyclists have become more vulnerable. They generate an average cost of £2,130,922 per fatal accident.

Across industry, construction and agriculture include the most perilous occupations, with premature deaths associated with falls from height; being struck by moving objects (including machinery and vehicles); and being trapped by something collapsing or overturning. Such incidents cost an estimated £1.6m per fatal injury.

Dangerous days

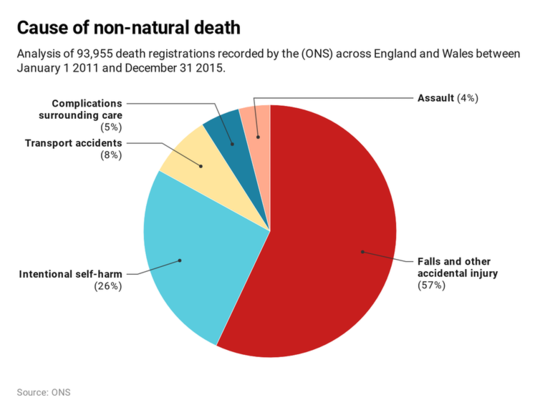

To better understand non-natural deaths, we analysed 93,955 death registrations recorded by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) across England and Wales between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015. We looked at each underlying cause of death to determine who had died due to “external causes of morbidity and mortality”.

Of these, 63% were men and 37% women, with an average age of 61 years. The two most common categories included falls and other accidental injury (57%), as well as intentional self-harm (26%). The remaining significant categories included: transport accidents (8%); complications surrounding care (5%), and assault (4%).

Researchers looked at each underlying cause of death to determine who had died due to ONS, CC BY

While unnatural deaths were consistently spread across the year, they did peak in December, when 8,416 died, and January (8,467). Transport accidents and assaults appeared to be more common on Friday, Saturday and Sunday, while deaths from intentional self-harm more commonly occurred on a Monday.

There were some further trends, specifically around gender and age. The average age for men to die from external causes was 55, while the average age for women was 70 years. This means men were more likely to die from unnatural causes prior to pensionable age, and women afterwards.

Those aged less than 65 years were also significantly more likely to die from transport accidents, intentional self-harm and assault, than those over 65 years. The analysis also found that men were significantly more likely to die from such incidents than women.

When to watch out

So how can this analysis reduce our risk of unnatural death? Is there a day we should stay at home and avoid a particular activity?

Unfortunately, the 1,826 days across our five-year sample failed to highlight a “most dangerous day”. The most fatalities for each year occurred on Saturday January 1, 2011 (77 deaths); Sunday January 1, 2012 (87); Sunday January 27, 2013 (84); Monday June 9, 2014 (81); and Tuesday March 3, 2015 (90).

But we did find that dangerous days were 2.2 times more likely to occur in winter than spring, and 1.3 times more likely to occur on the weekend in comparison to a weekday. Also, we found men are significantly more likely to die before the age of 65 from incidents such as traffic accidents, self-harm and assaults, when compared with women.

So you may be pleased to know that New Year’s day falls on a Wednesday this year. But if you are a man under 65 years of age, be particularly careful when crossing the road.![]()

About the Authors

Nathan Birdsall, Research Associate in Policing, University of Central Lancashire and Stuart Kirby, Professor of Policing and Criminal Investigation, University of Central Lancashire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

books_awareness