Robbie Drexhage/Wikimedia, CC BY

Robbie Drexhage/Wikimedia, CC BY

Little Richard was washing dishes at a Greyhound bus station in Macon, Georgia when he wrote Tutti Frutti, Good Golly Miss Molly and Long Tall Sally. The singer, who died Saturday at 87, sent the songs as demos to Specialty Records.

Soon he was having lunch with talent scout Robert “Bumps” Blackwell at a New Orleans nightclub, leaping onto the piano and belting out:

Tutti Frutti, good booty

if it don’t fit, don’t force it

you can grease it, take it easy

tutti frutti, good booty.

Watching the flamboyant performer sing about the pleasures of anal sex, Blackwell knew he had a hit.

The recorded lyrics were toned down for the conservative 1950s, but Little Richard’s wild whoops and falsetto screeches infused the song with the saucy spirit of the original.

Long Tall Sally then Tutti Frutti from the film Don’t Knock The Rock.

{vembed Y=LVIttmFAzek}

Preaching as Princess Lavonne

Born Richard Wayne Penniman and nicknamed for his smallness as a child, Little Richard was one of 12 children. He developed his charismatic singing, piano and performance styles playing in black and Pentecostal churches.

He was thrown out of home at age 13 by his father who didn’t like his loudness, in music or dress – a clear rejection of his queerness. As a teenager Little Richard performed in minstrel shows across the American South as the drag queen Princess Lavonne.

He brought his charismatic style and drag persona into his showmanship as Little Richard, with a camp style that enabled him to call himself the “king and queen of the blues”.

Historian Marybeth Hamilton argues Little Richard came out “of a black gay world and a tradition of black drag performance that formed an integral part of the culture of rhythm and blues”. Even when young audiences didn’t understand his lyrics, he “made the drag queen’s sly ironies part of every white teenager’s soundtrack”.

He described his songs as ballads that covered a range of experiences. The term “molly” in Good Golly Miss Molly referred to a male sex worker. Long Tall Sally was about a drunk woman Richard used to see as a child. Lucille was about a female impersonator.

Lucille in 1957.

{vembed Y=u0Ujb6lJ_mM}

Threatening the status quo

Little Richard confronted audiences with his suggestive lyrics and sexually charged sound, his gender bending falsetto, high hair and makeup, and his blackness.

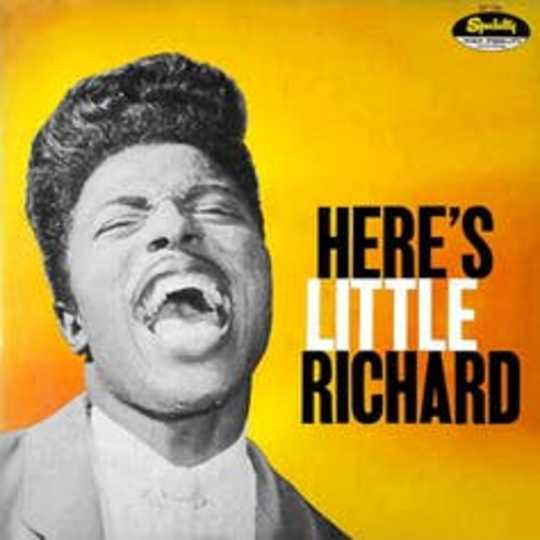

Journalist Jeff Greenfield recalled his parents’ horror when he picked up the 1957 debut record Here’s Little Richard.

On a yellow background, a tight shot of a Negro face bathed in sweat, the beads of perspiration clearly visible, mouth wide open in a rictus of sexual joy, hair flowing endlessly from the head.

In conservative, racially segregated, 1950s America, when interracial marriage was illegal, and homosexuality was a crime, Little Richard’s popularity embodied the perceived dangers of the new generation’s music. There was particular concern that young people would be influenced into alternative lifestyles including via mixing across lines of race and class at dance halls.

To counter the perceived threat he posed to conservative white America, Richard worked to present himself as so outré, so out there – dressing as the pope and the Queen at different performances – as to present no menace.

Little Richard’s 1957 debut album. Wikipedia/Speciality

Little Richard’s 1957 debut album. Wikipedia/Speciality

After he had a religious epiphany during his Australian tour, he took a break from music, returning in the 1960s. This was the first of many times he quit rock ‘n’ roll for God.

Despite having once described himself as gay and “omnisexual”, in the final years of his life Richard called gay and trans identities “unnatural”, a position that hurt some of his queer fans.

Generations

Little Richard’s urgent, intense delivery, the drama of his falsetto, his exuberant costuming and moves, his howling wildness, influenced generations of musicians and public figures including Muhammad Ali.

Artists who owe enormous debts to his influence include Tina Turner, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Otis Reading, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Patti Smith, Led Zeppelin, Elton John, Prince and Bruce Springsteen. Following news of his death, artists from Bob Dylan to Paul McCartney to Janelle Monáe posted tributes on social media.

From 'Tutti Frutti' to 'Long Tall Sally' to 'Good Golly, Miss Molly' to 'Lucille', Little Richard came screaming into my life when I was a teenager. I owe a lot of what I do to Little Richard and his style; and he knew it. He would say, 'I taught Paul everything he knows'. pic.twitter.com/96bOzphhs8

— Paul McCartney (@PaulMcCartney) May 10, 2020

In 1991, as part of the campaign to get Little Richard recognised with a Grammy award, David Bowie said, “without him, I think myself and half of my contemporaries wouldn’t be playing music”.

For younger generations, his name might not be as recognisable as those of his peers like Elvis Presley. This is in part likely the result of Richard’s own ambivalent relationship with rock ’n’ roll. But it’s also the result of the combined impact of racism, homophobia, and respectability politics. For some (including himself) he was at various times, too queer, too black, too feminine, too close to the devil.

And yet his gift lay, through music, in transmuting this otherness into a transcendent, shared permission to be free.

As one 1970 reviewer described his stage performance, Little Richard was “mesmerizing because he hits the cosmic mainline, a source of radiant energy that has the power to dissolve the ghosts of identity”.

As Little Richard sang it: “A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom”.![]()

About The Author

Rebecca Sheehan, Lecturer in the Sociology of Gender and Program Director of Gender Studies, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.