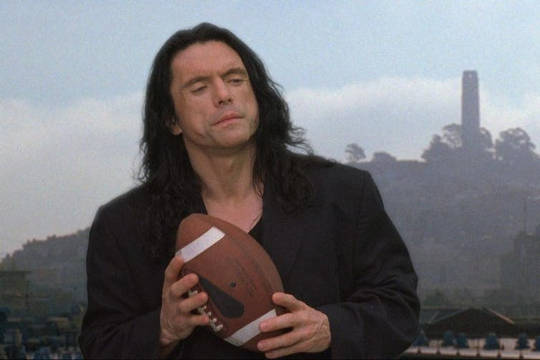

Tommy Wiseau clutches a football in ‘The Room,’ the 2003 film he wrote, produced and starred in. Wiseau Films

“The Disaster Artist” – which just earned James Franco a Golden Globe for his portrayal of director Tommy Wiseau – tells the story of the making of “The Room,” a film that’s been dubbed “the Citizen Kane” of bad movies.

Not everyone likes “The Room.” (Critics certainly don’t – it has a 26 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes.) But lots of folks love it. It plays at midnight showings at theaters across North America, and it’s a testament to a movie’s awfulness (and popularity) that, years later, it became the subject of a different movie.

We usually hate art when it seems like it’s been poorly executed, and we appreciate great art, which is supposed to represent the pinnacle of human ingenuity. So, this raises a deeper question: What’s the appeal of art that’s so bad it’s good? (We could call this kind of art “good-bad art.”) Why do so many people grow to love good-bad art like “The Room” in the first place?

In a new paper for an academic journal of philosophy, my colleague Matt Johnson and I explored these questions.

The artist’s intention is key

A Hollywood outsider named Tommy Wiseau produced, directed and starred in “The Room,” which was released in 2003.

The film is full of failures. It jumps between different genres; there are absurd non-sequiturs; storylines are introduced, only to never be developed; and there are three sex scenes in the first 20 minutes. Wiseau poured substantial cash into the film – it cost around US$6 million to make – so there’s some degree of professional veneer. But this only accentuates its failure.

Good-bad art doesn’t just happen at the movies. On TV, there was “Dark Shadows,” a low-budget vampire soap opera from the 1970s. In Somerville, Massachusetts, you can visit MoBA – the Museum of Bad Art – dedicated to paintings that are so bad they’re good. The poet Julia Moore (1847-1920) was ironically known as “The Sweet Singer of Michigan” for her deliciously terrible poetry. And the recent film “Florence Foster Jenkins” tells the true story of an opera singer with a tone-deaf voice so beloved that she sold out Carnegie Hall.

In good-bad art, it seems that the very features that make something bad – a horrible voice, cheesy verses or an absurd storyline – are what end up drawing people in.

So we need to look at what’s “bad” about good-bad art in the first place. We equated artistic “badness” with artistic failure, which comes from failed intentions. It occurs when the creator didn’t realize their vision, or their vision wasn’t good in the first place. (MoBA, for instance, requires that its art comes from genuine attempts.)

You might think a movie’s bad when it’s very silly, whether it’s “Snakes on a Plane” or “Sharknado.” You might think that “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” is bad because it looks schlocky.

But these films aren’t failures. “Snakes on a Plane” is supposed to be silly; “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” is supposed to look schlocky. So we can’t categorize these works as so bad they’re good. They’re successful in the sense that the writers and directors executed their visions.

Our love for good-bad art, on the other hand, is based upon failure.

How not to appreciate bad art

So how could artistic failure ever be the basis for goodness?

A pretty natural answer here is that we like good-bad art because we take a general pleasure in the failure of others. Our pleasure, say, at MoBA, is a particular kind of schadenfreude – the German word for taking joy in another’s misfortune. This view doesn’t have an official name, but we could call this “the massive failure view.” (The great Canadian humorist Stephen Leacock held this view, arguing that singer Julia Moore’s earnest ineptitude made her work funnier.) If this view were right, our enjoyment of “The Room” would be morally suspect; it’s not healthy to get our kicks from the misfortune of others.

Fortunately for lovers of good-bad art, we believe this “massive failure theory” of good-bad art is false, for two reasons.

First, it doesn’t feel like we are enjoying pure failure in works like “The Room.” Our enjoyment seems to go much deeper. We laugh, but our enjoyment also comes from a kind of bewilderment: How could anyone think that this was a good idea?

On his podcast, comedian Marc Maron recently interviewed Franco about “The Disaster Artist.” Maron was a little uneasy about the film; to him, it seemed as if Franco were taking a gleeful delight in Wiseau’s failure.

But Franco resisted this: “The Room” isn’t just great because it fails, he explained; it’s great because it fails in such a confounding way. Somehow, through its many failures, the film totally captivates its viewers. You find yourself unable to look away; its failure is gorgeously, majestically, bewildering.

Second, if we were just enjoying massive failure, then any really bad movie would be good-bad art; movies would simply have to fail. But that’s not how good-bad art works. In good-bad art, movies have to fail in the right ways – in interesting or especially absurd ways.

Some bad art is too bad – it’s just boring, or self-indulgent or overwrought. Even big failures aren’t enough to make something so bad it’s good.

The right way to appreciate bad art

We argue that good-bad artworks offer a brand of bizarreness that leads to a distinct form of appreciation.

Many works – not just good-bad artworks – are good because they are bizarre. Take David Lynch’s films: Their storylines can possess a strange, dreamy logic. But good-bad art offers a unique kind of bizarreness. As with the films of David Lynch, we’re bewildered when we watch “The Room.” But in Lynch’s movies, you know that the director at least intentionally included the bizarre elements, so there’s some sense of an underlying order to the story.

In good-bad art like “The Room,” that underlying order falls out from beneath you, since the bizarreness is not intended.

This is why fans of good-bad art strongly insist that their love for it is genuine, not ironic. They love it as a gorgeous freak accident of nature, something that turned out beautifully – not despite, but because of the failure of its creators.

Maybe, then, when we delight in good-bad art, we are taking some comfort: Our projects might fail, too. But even beauty can blossom out of failure.

About The Author

John Dyck, PhD Student in Philosophy, CUNY Graduate Center

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon