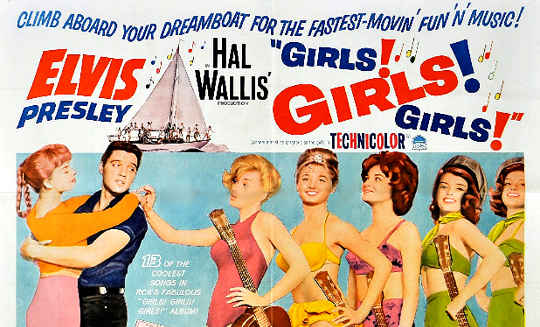

Shake your money maker. Wikimedia Commons

This summer marks 40 years since the death of Elvis Presley. In the decades since the singer finally left the building, the hits have continued, his home at Graceland is now a top tourist attraction, and he is regularly listed as one of the top earning dead celebrities by Forbes.

From the moment he burst onto the music scene in the 1950s, to the late Vegas years of garish jumpsuits, Presley’s career tells a host of intriguing tales. From an economics point of view, however, his roster of entirely forgettable, but wildly successful movies offers the most fertile ground.

Many readers will be familiar with the existence of Elvis’s films, even if the plotlines don’t spring immediately to mind. Between 1956 and 1972, he made 33 movies, and in all but one he took the starring role. And they were popular. In today’s money, the total box office receipts equate to over US$2.2 billion, and that is for the US alone.

All Shook Up

Each film typically cost around US$2m to make, a reasonable sum in the 1960s, equating to around US$15.5m in today’s money (but only around 10% of the budget of Disney’s Moana). On average, they grossed around three times that at the US box office. Hollywood saw them as a safe money-spinner, the domestic market alone guaranteed a profit.

In some ways, Elvis’ films were the precursor to today’s music videos. They followed a tried and tested formula, generally featuring Elvis in exotic locations such as Hawaii, Acapulco, or Las Vegas, and performing an album’s worth of songs in the midst of adventures involving racing cars, flying planes, or deep sea diving.

From a marketing perspective, film making was a win-win situation, a virtuous circle of marketing gold. The films advertised Presley’s latest recordings to his fans. Seeing the film would then encourage fans to buy the soundtrack album, while radio plays of recordings from the soundtrack would prompt them to go and see the film.

And there was the added bonus that fans all around the world could watch Elvis perform without him having to travel. The film companies generally paid the costs for recording the soundtrack, as well as the publicity photos that went on the sleeves, meaning that RCA, Elvis’ record company, had the majority of their costs covered too.

{youtube}uOF9lzGLz-8{/youtube}

The films may have been sound financial investments, but their artistic ambition didn’t impress the critics. The focus on profit meant that budgets were squeezed. Filming schedules were very tight, typically four weeks, although films such as Kissin’ Cousins were made in less than three weeks by a producer known as the “king of the quickies”.

The songs also got worse, soundtrack recordings such as Yoga is as Yoga Does, and A Dog’s Life were a far cry from the hits that made him famous. In his comprehensive overview of Elvis’ recording career Ernst Jorgensen quotes one of the Jordanaires’ (who sang backup on most of these recordings), who recalled: “the material was so bad that [Elvis] felt like he couldn’t sing it”.

{youtube}https://youtu.be/Pro7XpRpU04-8{/youtube}

They didn’t all lack quality. Presley’s earlier films are generally held in greater esteem, with Jailhouse Rock, King Creole and a few others considered to be good examples of the genre.

Heartbreak Hotel

Now, we can argue the toss over whether to judge the movies by financial or artistic success. But Elvis’ focus on filmmaking, as opposed to live appearances, has been convincingly presented as one of the reasons for his mid-60s decline. As Elvis stuck to his formula, the music scene changed. While the Beach Boys were making classic albums like Pet Sounds, Elvis was singing about pet dogs, cows and shrimps. Half a century ago, when the Summer of Love got into full swing, The Beatles released the seminal Sgt Pepper album. Elvis was inviting everyone to a clambake.

{youtube}RhSSgWmfFk0{/youtube}

By the late 1960s, Presley’s popularity had waned; movie box office receipts fell, critics were less impressed with each release, and the records from the soundtracks no longer climbed as far up the charts. Strangely though, at the same time, film companies such as MGM and United Artists, were paying ever higher fees for his services. The chart below shows both the box office receipts and the fee Elvis received for the film. Over time we can see that the fees Elvis earned were rising as the box office receipts were declining.

Hollywood appeared to be paying for his star power, which in turn pushed them towards making cheaper, low quality films. Economic theory would predict that as demand falls, the price, Elvis’ fee, should also fall. Yet, it appears that his fame insulated him somewhat from market forces, with film companies prepared to cut other costs in order to secure their star.

Presley’s film career is often remembered as playful and flimsy, and rightly seen as an exercise in marketing first and foremost. Yes, US$2.2 billion is a lot of money, but could Elvis’ film career been more fulfilling? There is a long line of singers who have made a successful film career for themselves from Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin through to Tom Waits and Justin Timberlake.

A 1977 article in Rolling Stone magazine revealed that those who worked with Presley felt he had more to give. Norman Taurog, who directed nine of his films, felt Elvis never reached his peak. Don Siegel, director of Flaming Star (and later on Dirty Harry), felt he only went along for the ride. Robert Abel, co-director of Elvis on Tour, neatly summed it up when he said: “[Elvis] was basically an incredibly fine actor with a lot of vulnerability and a lot of humanity that he could have communicated in his films. And occasionally he did”.

![]() Yet, the films are mostly fun, and they mean we still get to see a youthful Elvis perform classic songs such as Teddy Bear, Jailhouse Rock or Can’t Help Falling in Love. And don’t forget, A Little Less Conversation – the song which was remixed and launched into an entirely new generation in 2002 – was originally found in the 1968 movie Live a Little, Love a Little. Ultimately, these films served their purpose at the time, and have helped to give The King longevity into the 21st century.

Yet, the films are mostly fun, and they mean we still get to see a youthful Elvis perform classic songs such as Teddy Bear, Jailhouse Rock or Can’t Help Falling in Love. And don’t forget, A Little Less Conversation – the song which was remixed and launched into an entirely new generation in 2002 – was originally found in the 1968 movie Live a Little, Love a Little. Ultimately, these films served their purpose at the time, and have helped to give The King longevity into the 21st century.

About the Author

Andrew Johnston, Principal Lecturer in International Business and Economics, Sheffield Hallam University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon